|

|

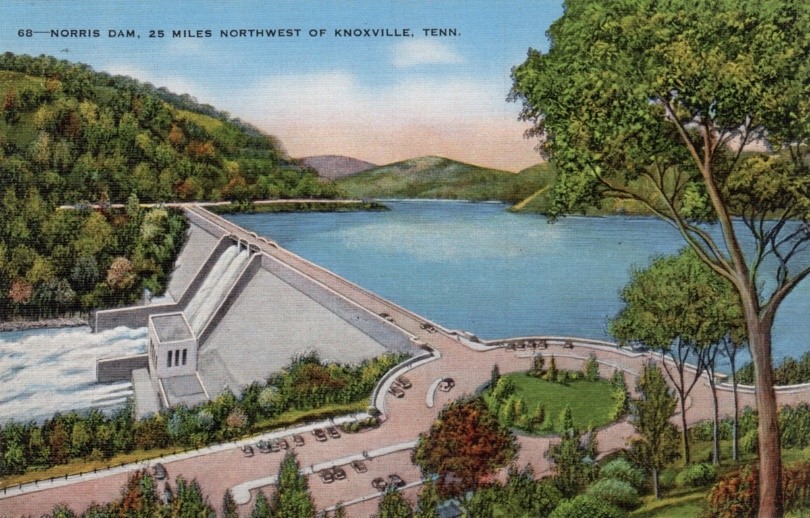

Norris Dam Postcard | courtesy Knoxville History Project/Sam Furrow Knoxville Postcard Collection Collection |

Imagine you're a tourist in Knoxville one century ago, in 1920. What would draw you here? And if you were here for business, what would you do while you were in town?

The Smoky Mountains? They were there, visible on a clear day, but there was no national park up there. To get very close, you'd have to do some trespassing. And much of it was an industrial site, owned by lumber and mining companies.

The recreational lakes? Douglas, Watts Bar, Fort Loudoun, Norris? They were unpredictable rivers, sometimes high, sometimes low. Boating was problematic, houseboats, lake houses, and waterskiing unheard of.

How about college sports? They existed, at UT and Knoxville College, but you didn't hear much about conference or national championships in those days. Even UT had an inferior, sub-regulation field that had crude bleachers, like a small high school's field today, but not nearly as good.

Festivals? Knoxville had a few, over the years, but nothing that had caught on, that happened every year, except for the annual East Tennessee Division Fair, forerunner to the Tennessee Valley Fair.

Even without all that, Knoxville was still a tourist destination for some, at least. One attraction was that downtown had probably the highest concentration of shopping in the Southern Appalachian region. Some "tourists" would come and book a week at the Farragut Hotel (present day Hyatt Place), or the Atkin, and just spend the week shopping and going to movies. For many small-town wives and mothers, it was an escape, and hard to think of anything better. They'd buy Knoxville postcards and send them home to envious friends.

|

| Whittle Springs Postcard | courtesy Knoxville History Project/Sam Furrow Knoxville Postcard Collection Collection |

Knoxville was also a center for springs resorts, which were probably more popular than beaches for much of America. Some advertised "medicinal" qualities to the springs that usually flowed by a hotel with lots of porches for relaxing, some didn't. In 1920, Knox County had Whittle Springs Neubert Springs, and several other within a short carriage or railroad ride. Elkmont was famous by then, but it was about the only place in the Smokies that people actually went.

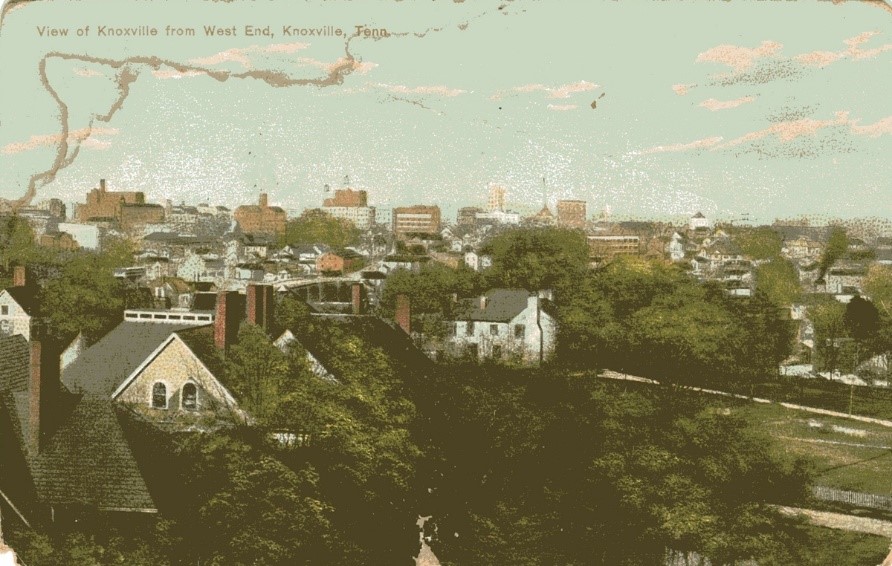

But even in 1920, Knoxville liked to think it had its own attractions. The City Directory offered "tours" of the city. There were 13 of them, each about an hour long, and all of them left from downtown. They were called streetcar routes.

Every year, the city or Chamber of Commerce would list sites of interest that were visible on streetcars, and indicate which side you should sit on if you wanted the best view. There were 13 routes reaching from the mental institution on the west (now it's Lakeshore Park, but even then it was picturesque, a green campus with old buildings and big trees) to Chilhowee Park on the east, with its lake--in 1920 the recommendations mentioned the National Conservation Exposition, which had closed in late 1913, but perhaps as late as 1920, people just wanted to see where it happened. Or Fountain City on the north, with its own lake. Some streetcars crossed the bridge to go to Island Home, where there was another suburban park by the river.

Whittle Springs, the big hotel with its big swimming pool and golf course, was the attraction on the #4 route.

|

|

Fort Sanders Postcard | courtesy Knoxville History Project/Cindy & Mark Proteau Collection Collection |

The #7 Highland Route took you by. It wasn't the hospital, which wasn't there yet, or the neighborhood, which was generally called "West End." In 1920, "Fort Sanders" was the last ruins of the once-massive ramparts of the actual Union fort, from 1863, when scores of Confederates died attacking it. To see it, still visible at the top of the hill, just west of 17th Street, they recommended you sit on the left side of the Highland Avenue car. It wouldn't be there much longer, in the popular neighborhood where it seemed as if every acre was getting developed. But if you wanted a good view of the nearby New York Highlanders monument on 16th Street, you'd take another car, the #10, which went to Circle Park, which was nice, too, a public park for picnics and ball games long before it had any association with a university.

The #3, Jackson Avenue, presented gritty scenes of the Stockyards on Willow Street, but also the old Circus Grounds and Brewers Park, the African American baseball field.

The Lyons View car offered a view of a big bend in the Tennessee River that had drawn artists for decades. It also hosted what was then known as the Eastern Hospital for the Insane. Eastern State, as it would later be known, with its big trees and old brick buildings, was prettier than most college campuses. Of course, it had a big iron fence around it.

Some of Knoxville's attractions in 1920 require a little explanation today. Among the city's "Principal Places of Interest" according to the Chamber, was "The Grave of 'Our Bob.'" "Our Bob" was Robert Taylor, arguably Tennessee's biggest celebrity, the governor who was also a stand-up comedian / motivational speaker, author, fiddler, and later senator, had died suddenly in Washington in 1912, and his burial at Old Gray attracted a reported 40,000 people, a number that seems more credible if you see photographs of it. It was perhaps the biggest funeral in Tennessee before that of Elvis, 65 years later. In 1920 people still came to Knoxville to both his grave and his former home, a palatial Victorian at the corner of Fourth and Gill--the Chamber listed the address, 803 N. Fourth, even though it had not been Taylors's home in many years. That house burned down in the 1980s. Today, even his tourist-attracting grave is gone--in the 1930s, the family moved it to the old homestead near Johnson City. But today, there's still a step leading up to an empty plot, marked TAYLOR. (His grandson, the Pulitzer-winning author Peter Taylor, wrote his final novel, In the Tennessee Country, partly inspired by legends about Robert Taylor.

|

| Parson Brownlow Residence Postcard | courtesy Knoxville History Project/Sam Furrow Knoxville Postcard Collection Collection |

Parson W.G. Brownlow's home was still standing in 1920, on East Cumberland. Tennessee's vengeful but effective postwar governor was a national figure of some renown, especially among Republicans. Presidents William McKinley and Teddy Roosevelt had made a special point to visit his rambling frame house on the east side of downtown. It was torn down later in the 1920s for an apartment building--which was itself torn down about 30 years later, during Urban Renewal.

Not far from there was another tourist attraction listed by the Chamber, the "First Capital of Tennessee," at the corner of State and Cumberland. It was a gray old wooden 1790s building that had that signage on it, whether it was accurate or not, it was the only alleged remnant of Knoxville's quarter-century as a state capital before 1820. Nonetheless, it was torn down for parking only a few years after the Chamber recommended it as a site to visit.

They also recommended you behold "The Oldest House in Knoxville." They didn't tell you which one they meant, but it's likely they were talking about the building we know today as Blount Mansion. It was the former home of a signer of the U.S. Constitution who later became the governor of the Southwestern Territory before it became Tennessee. That name wasn't familiar in 1920, when folks just knew the ca. 1792 frame structure it as a very old house. Only after 1925--when it was almost torn down for hotel parking--did it become a preserved historic site that you could actually visit.

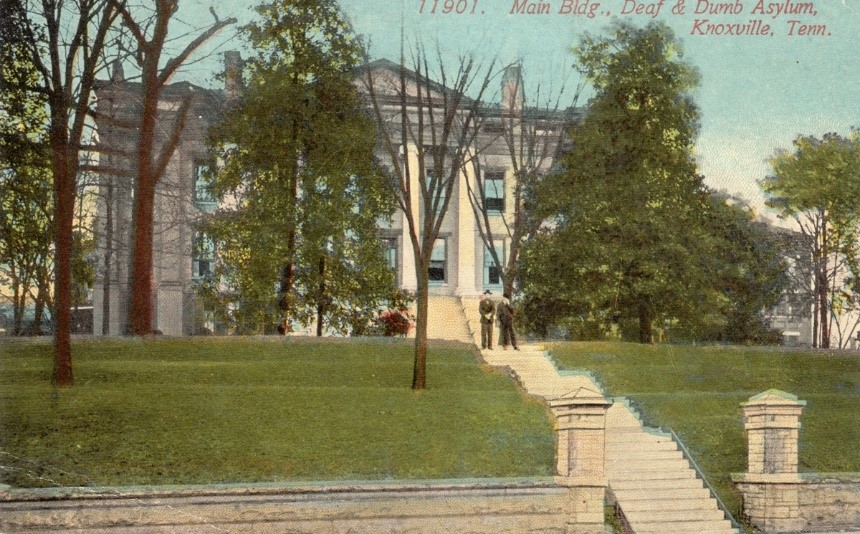

Also downtown was what was then known as the Tennessee Deaf and Dumb School--later known as Tennessee School for the Deaf. In 1920 it was of more than passing interest, because it was one of the oldest deaf schools in America, and it was located in one of the oldest buildings downtown, the 1848-1851 structure on the hill near the L&N Railroad Station. We're lucky it's still there, now occupied by the Lincoln Memorial University School of Law (and a stop on the Civil War Driving Tour).

|

|

Tennessee School for the Deaf Postcard | courtesy Knoxville History Project/Cindy & Mark Proteau Collection Collection |

Cemeteries were attractions, especially Old Gray, with lovely Victorian statuary, like the Albers fountain (missing for many years but recently rebuilt) and its largest grave, that of Parson Brownlow--as well as the very different National Cemtery, next door, with its lofty Union statue, said to be the largest in the South, and thousands of Civil War, Spanish-American War, and now World War I graves.

Factories were built to behold in those days, and sometimes people wanted to see the William J. Oliver Mills--it had been involved in providing machinery for the Panama Canal construction--Appalachian Mills, and the East Tennessee Packing Co., all of which were visible from the #5, which went across the Gay Street Bridge to South Knoxville. The Southern Railway Shops--the Coster Shops--were a huge plant on the north side of town that serviced Southern passenger and freight trains.

The University of Tennessee was recommended, even though it didn't have much open to the public--its ivy-covered brick buildings, some of them still showing the scars of cannon fire from the Civil War, were worth just beholding on its already-famous Hill.

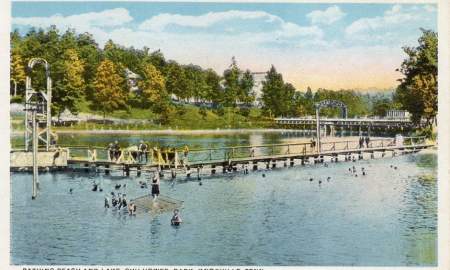

Bathing at Chilhowee Park Postcard | courtesy Knoxville History Project/Sam Furrow Knoxville Postcard Collection Collection

Chilhowee Park, Fountain City Park, Island Home Park--and Luttrell Park. You may never have heard of the last one. It was a riverside park established by the Luttrell family on the south side of the river. It was a lush, green place, popular with Boy Scouts.

The classic old Marble post office, built just after the Civil War, was on the list of Knoxville's tourist attractions in 1920, too. Also called the Custom House, it's still one of the city's main attractions--it houses the Museum of East Tennessee History.