Blount Mansion

Each year, the Historic House Museums of Knoxville celebrate Statehood Day by inviting the public into the hallowed halls of their stately manners, antebellum mansions, and frontier fortifications to experience the stories of those who lived there firsthand. On June 3, 2023, not only can you visit our sites for free, but you can also join in on a bevy of other activities (many of those as a part of Bike Boat Brew & Bark!)

- Blount Mansion will have free admission and family activities.

- Marble Springs will be hosting their regular Statehood Day Craft Fair and Festival from 10:00 am - 4:00 pm where guests can enjoy historical demos and live music, indulge with local craft vendors, and partake in other fun family activities.

- Mabry-Hazen House will have free admission and rifled musket firing demonstrations at 11:00 am and 1:00 pm.

- James White's Fort will have free admission and historical demonstrations.

Whether you have an hour or the whole day, there's something for everyone to experience during this year's Statehood Day celebrations! We can't wait to see you there!

Statehood Day commemorates Tennessee’s admission to the union as the sixteenth state on June 1, 1796. While it’s true that each of the fifty states can celebrate such a “birthday,” if you will, Tennessee can take pride in being the first to gain its statehood in a completely new way. And the idea was born at Blount Mansion in the heart of downtown Knoxville.

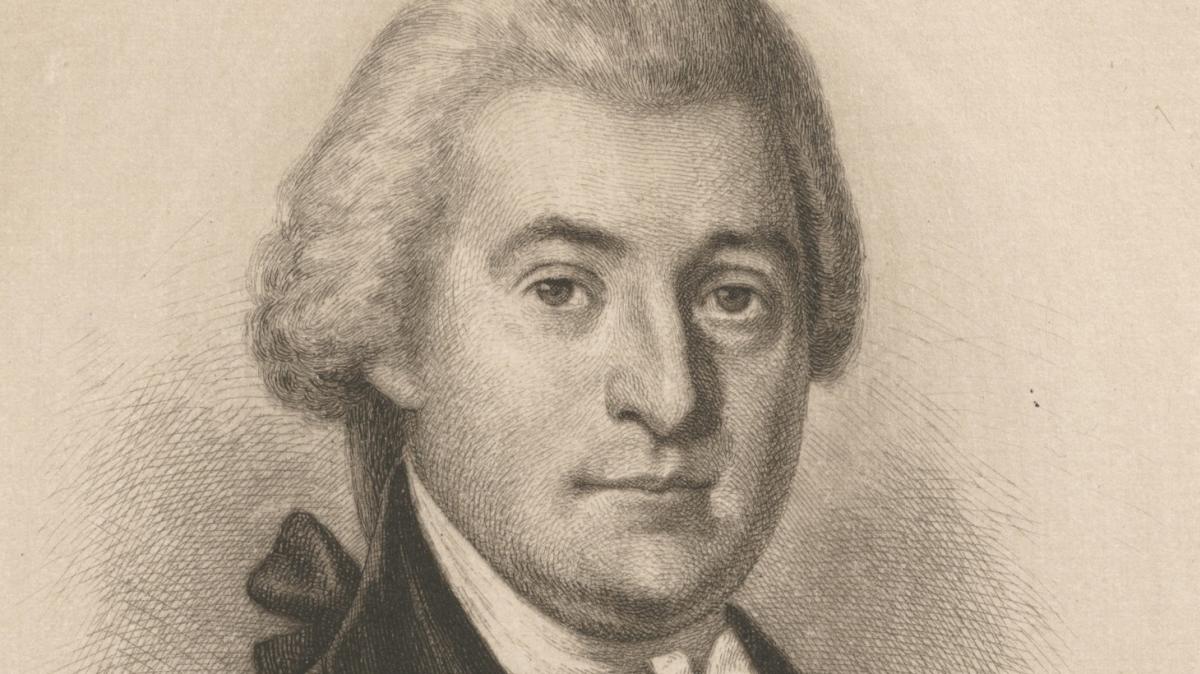

Portrait of William Blount from the Collection of New York Public Library

William Blount came over the mountains from his native North Carolina in 1790 to serve as governor of the Southwest Territory, as our area was then known. The land, which had belonged to North Carolina, was now under the control of the federal government based in Philadelphia (Washington, D.C. was officially created in 1790, but the president and Congress did not move there until a decade later). Blount had a wooden frame house constructed on a bluff overlooking the river, on land owned by local pioneer James White. Blount’s handsome home, though not a mansion in the modern context, was the first fancy residence in a region dotted with log cabins and crude stockades. The property served simultaneously as the Blount family home and the territorial capital. A small detached single-room structure a stone’s throw to the southeast served as Blount’s office, and it was in this unassuming little building that the process of Tennessee statehood began.

Map of Southwest Territory

Folks from this area had already made one stab at statehood a few years earlier, in 1785, when they created the short-lived State of Franklin in what is now northeastern Tennessee. The Franklinites’ effort failed when they failed to gain the support of two-thirds of Congress, and North Carolina re-asserted control over the land. Blount’s plan was no less bold, but it succeeded.

Blount and his allies were required to meet a prescribed benchmark in order to attain statehood for the territory—a threshold spelled out by Congress in laws creating the Northwest Territory in 1787, and replicated for the Southwest Territory. Once it could be proven that at least 60,000 male inhabitants lived within its borders, the territory was entitled to petition for statehood. A census taken in late 1795 revealed that the territory’s male population exceeded that amount by more than 17,000 men. Blount wasted no time, calling a constitutional convention in Knoxville that December. In January of 1796, the 55 delegates drafted a state constitution, and the drafting committee is believed to have met in the little office behind William Blount’s house. When they signed the document in February, the entire group had to gather in David Henley’s large law office nearby, but the groundwork was laid in the same small office from which William Blount had governed the territory. The petitioners decided to christen their proposed state Tennessee, a name whose origin is shrouded in mystery but clearly has Native American origins (the word first appears as “Tanasqui” in a report by Spanish explorer Juan Pardo in 1767).

Though the would-be Tennesseans had jumped through all the prescribed hoops in their quest for statehood, their fate lay in the hands of the federal government in Philadelphia, more than 600 miles away. William Blount, the visionary who came over the mountains to create a new government in the wilderness, was not inclined to wait on Congress to act. Instead, Blount and his fellow visionaries created an entire state government, complete with a legislature, electing John Sevier the first governor and William Blount and William Cocke U.S. Senators. In April 1796, Blount and Cocke traveled to the national capital to make their case for immediate statehood.

Exterior of Blount Mansion with Gay Street Bridge in the Background

In a scenario that presaged today’s frequently-divided federal government, the two houses of Congress were soon locked in a bitter dispute over how to respond to the petition. In this age before the arrival of Democrats and Republicans, Congress was split between Federalists and Anti-Federalists, with the former holding sway in the House of Representatives and the latter in the Senate. The Anti-Federalists favored Tennessee’s admittance, while the Federalists were opposed (This had to do with the belief that Tennessee’s citizens, who would be added to voter rolls once statehood was attained, would swell anti-Federalist ranks and alter the balance of power). A month of bitter debate ensued, but in the end, Blount and his compatriots carried the day, and Tennessee gained admittance to the union as our nation’s sixteenth state that June.

Blount’s brash method—essentially showing up in the national capital uninvited and introducing himself as the senator from the newest state—came to be known as the Tennessee plan. While some new states waited for Congress to open the door and invite them to join the union, others took notice of Tennessee’s success and followed suit. Six additional territories organized themselves under a version of the Tennessee plan and similarly forced Congress to admit them as states. These included Michigan, Iowa, California, Oregon, Kansas, and Alaska. A seventh territory, New Mexico, attempted the Tennessee method unsuccessfully. The Tennessee Plan remains a model to this day, with activists in Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia advocating a similar path to statehood for the territory and the district.

William Blount’s Office

It all started in Knoxville in 1795, in William Blount’s tiny little office behind his house overlooking the river downtown. While you’re always welcome to come tour Blount’s house and his office and reconstructed kitchen any day Tuesday-Saturday (barring special events), we’d like to issue you a special invitation to visit us free of charge on Statehood Day—June 1st, 2019—the 223rd anniversary of Tennessee’s statehood and the success of William Blount’s audacious plan. Who knows? Maybe you’ll be inspired to dream big dreams of your own. At the very least, you’ll take pride on the Volunteer State’s first claim to fame on the day when it happened and in the room where it all began.

Post originally written by Michael Jordan in 2019, updated in 2023 by Jennifer Lee