November is National Native American Heritage Month, and visitors often ask about Native American culture and history in Knoxville and the surrounding area. This post by historian Jack Neely explains the connections between Cherokee Boulevard (the main thoroughfare through the Sequoyah Hills Neighborhood to the immediate west of downtown) and the Indigenous people who lived in this region.

A discussion of Native American culture in Knoxville comes with some challenges. There were no permanent Cherokee villages in Knox County, and probably none in the familiar metro area. The largest part of the Cherokee Nation was in Northern Georgia, but a very significant northern part of it, the Overhill Cherokee, was in East Tennessee, mostly in Monroe County (south of Blount County, which neighbors Knox County to the south).

However, the Cherokee often hunted in the area that became Knoxville and considered this whole region part of their homeland. After its founding—which followed a major convention of Cherokee chiefs here to discuss the Treaty of the Holston in 1791—at least a few became familiar with the city itself.

Centuries before the Cherokee was an earlier culture known to archaeologists as the Woodlands culture, and scholars say it’s likely that they did live here, about 1,000 years ago. Considered prehistoric, they had no written language and left no records of what they called themselves. But they did leave creative pieces of pottery, showing an interest in the natural world around them, and some imagination. They often left steep mounds of earth. Here they’re mostly near the river. These are believed to have been burial mounds prepared, like the pyramids, to hold the remains of notable members of a tribe.

There aren’t many cities that have accessible Indian mounds. There may be four or five remnants of mounds in Knox County, some of them in hardly discernible ruins. The best-preserved mound in the region happens to be on the University of Tennessee’s agricultural campus, alongside Joe Johnson Drive. Often pointed out to tourists visiting Knoxville in the late 19th century, it was always there, and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978—but still unknown to most UT students, and to most Knoxvillians.

The second best, smaller and eroded, perhaps by agriculture, is in the median of the scenic riverfront road called Cherokee Boulevard. It overlooks a popular boat launch, and a park where people play frisbee football and throw tennis balls for Golden Retrievers. Hundreds of people jog over the top of that mound every day. More about that later.

Their presence leaves us with a historical asset, not just to help us understand regional history, but to give perspective to the deep Native American history of the continent. Our mounds are the subject of a new exhibit to be hosted by UT’s McClung Museum; now in the early planning stages (the exhibit may be complete in the fall of 2023). McClung Museum, which was founded in large part to preserve and study Native American relics disrupted by Tennessee Valley Authority projects, is already the best place in Knoxville to learn about Native American culture. Maybe we’ll understand them better by then. However, the Woodlands mounds they left confused generations of Knoxvillians, who assumed the mounds were left by the Cherokee.

Panther Fountain in Sequoyah Hills/Talahi Park

In Knoxville’s early years, Cherokee names were not attractive to businesses and developers. In the late 19th century, though, America saw a new fascination with Native American culture, through poems and books that made Cherokee culture sound sympathetic or even romantic. By 1890, the word “Cherokee” started popping up all over town, as a name for places and businesses run by white people. UT’s Cherokee Farms complex, across the river from campus, was originally to be a private riverside subdivision called “Cherokee.” (There may be scant ruins of a mound over there.) That plan was abandoned during an 1890s recession, but soon, Knoxville’s first country club was named Cherokee, in 1907.

When developers created Sequoyah Hills on a river peninsula in the 1920s, they carved out a new riverfront boulevard, that had one unusual feature—a prehistoric Indian Mound. Apparently inspired, they named the boulevard “Cherokee.”

Talahi Park in Sequoyah Hills

|

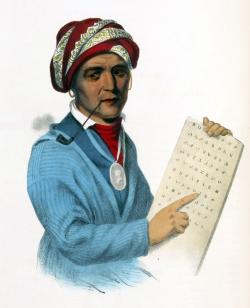

| Cherokee Scholar Sequoyah |

In 1926, a more idealistic companion development, Talahi, took the Cherokee motif a step forward, incorporating some specific Native American lore, as well as use of the Cherokee “Thunderbird” imagery in the fencing, and streetlamps adorned with references to the myth of the Cherokee water spider, said to be the bringer of fire. Both of the developments left streets with Native American and pseudo-Native American names, like Taliluna, Iskagna, Keowee, Kennesaw.

Developers claimed at the time that the peninsula was once the home of the Cherokee scholar Sequoyah, creator of the first Native American alphabet and, by implication, the first Native American written language. Hardly any Native American—in fact, hardly any American—has had that kind of influence. It’s not surprising that the North Carolina developers who laid out Sequoyah Hills said they named it for the “old Indian chief of the Cherokees who once dwelt on the property.”

However, Sequoyah, the venerable “old Indian chief,” has no known association with Sequoyah Hills, or any other part of Knoxville. He was born at Tuskegee, one of several Cherokee villages along the Little Tennessee River, in what’s now Monroe County (The Sequoyah Birthplace Museum is in Vonore, less than an hour from downtown Knoxville). It’s not unlikely that he may have visited Knoxville, which was the white man’s capital when Sequoyah was a young man, and a significant trading center. Later, Knoxville paper mills would provide the paper for the first Cherokee newspaper, the Phoenix. But by then, the restless scholar Sequoyah had moved west of the Mississippi (he was sojourning in Mexico when he died).

Of course, most Tennessee and Georgia Cherokee moved west in the 1830s, when their Nation was forced to move to Oklahoma, in the tragic Trail of Tears (learn more about the Trail of Tears in this region at the East Tennessee History Center). So—there were never Cherokee villages, and probably no Cherokee burial grounds in what we know as Knoxville. Sequoyah Hills was never the birthplace, residence, or burial place of Sequoyah.

Still, legends and exaggerations often have some kernel of truth. References to Indian traders in Knoxville persist for years after Indian Removal. Individuals were not forced out of U.S. society. They just no longer had tribal sovereignty over their ancestral lands. A few, for whatever reasons, stayed behind, opting to make their way as a very small minority in white-dominant culture.

Indian Mound in Sequoyah Hills

Indian Mound in Sequoyah Hills

A few stray references in a diary and family lore seem to affirm that a small band of Cherokee were living at Looney’s Bend—what’s now Knoxville’s Sequoyah Hills—in the early 19th century—and remained there after Indian Removal into the late as the 1840s and ‘50s, perhaps living off small farms, as some African American subsistence farmers in the same general area did—but also weaving baskets, in the envied Cherokee style, and selling them on Kingston Pike.

Crescent Bend

In 1842, four years after the Trail of Tears, Drury Paine Armstrong took a Sunday afternoon walk down the riverbank from his home, Crescent Bend, (which survives today as a museum house open to the public), and was interested to encounter “an encampment of Cherokee Indians, in number 10 … Found them making cane baskets. Had on hand … for sale perhaps 100 baskets. They seemed civil and well-disposed and rather inclined to myrth [sic] than sadness.” It’s not the only reference from that era to Indians selling baskets along Kingston Pike.

Armstrong noted that he found them about a mile downstream from his house—which would have put them approximately in the neighborhood that, 80 years later, developers endowed with a Cherokee theme.

To learn more about Native American culture and history in Knoxville, please visit the East Tennessee History Center.