|

| Wait for Field courtesy of University of Tennessee |

“Without a doubt,” wrote a Sentinel sportswriter in 1920, “Knoxville can lay claim to first honors when it comes to the worst football field in the world.”

Old Wait Field was a Southern Conference joke. Most universities in the Southeast that had a competitive football team had at least a decent field to play on. Wait Field, located at the southeastern corner of Cumberland Avenue and Fifteenth, was the best UT had to offer. The local press sometimes called it the “alleged” athletic field.

Part of the problem was the Hill. It’s impressive to have a college on top of a steep hill, as UT had been since 1828, but it didn’t allow for flat spaces required for athletic competition. UT was not just hilly, much of the area around it was crossed by rocky creeks. UT athletes traveled far from campus to find good athletic fields, as far away as Chilhowee Park, on the east side of town, or the old horse-racing track upstream, on the south side of the river near Island Home, or old Baldwin Park near Mechanicsville.

The old quad at the very top of the hill, right in the center of several academic buildings, had seen some informal track and field competitions, back in the late 1800s, and a few early football scrimmages, back when people were still learning the rules. But it wasn’t big enough for much, especially not football—a field goal would likely go through a math professor’s window—and by the early 20th century, the space was occupied by a large “pine palace” called Jefferson Hall, intended to be temporary, for special events.

Wait Field was a partial solution that arrived in 1908. It was well downhill from there, on the northwestern side of the Hill. But part of its problem was that it wasn’t completely clear of the Hill. One corner had a bit of a slope. It had been passable by the standards of 1908, when it was built, and named for Dr. Charles E. Wait, president of UT’s athletic association, and intended as an honor to a professor much admired. However, Dr. Wait may have had reason to regret the association. As football became more popular after World War I, its deficiencies became more and more obvious. It tended to get muddy, and it may have been erosion that brought the stone to the surface. Wait Field became a laughingstock. One sportswriter referred to it as “that hard, sun-cracked, rocky, cindery, dusty old dump.”

Wait Field was only four years old in 1912 when a cadre of UT supporters organized an effort to purchase property for a real, modern, and completely legal athletic field. Among the charter subscribers were UT professors Brown Ayres, Charles E. Ferris, and J.D. Hoskins (all of whom are, today, remembered with UT buildings named for them), as well as Knoxvillians Cary Spence, merchant and war hero who had been a notable athlete in his youth; major wholesale merchant and historian C.M. McClung; and David Chapman, who in years to come would become famous as the leader of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park movement. They thought a modern athletic field would raise the university’s stature, and cited as examples the superior athletic facilities of Harvard, Yale, Princeton—and Vanderbilt, UT’s arch-rival. In the new 20th century, it appeared football and a good place to play it was the sign of a respectable university.

|

| Cartoon of Shields is from "Men of Affairs, 1921" McClung Historical Collection |

They needed about seven acres. It couldn’t be on campus, because the campus was all on a hill, but it would be nice if the new field were very near campus.

Coordinating the fundraising effort was prominent attorney Robert S. Young. They met frequently in 1914, sometimes at the old Imperial Hotel on Gay Street. UT President Brown Ayres appealed to “any citizen” who wanted to help by purchasing a $10 share. It was to be a community asset, something the whole city could be proud of.

Fundraising is often slow, even when it’s not interrupted by World War I and the Spanish Flu pandemic. After seven years, they still hadn’t raised nearly enough to make a modern football field a reality. By some accounts, the original effort was tilting toward failure.

But in July 1919, seven years after the effort started, elderly banker William S. Shields “stepped into the breach,” as they said, with a surprise donation of $25,000, to be matched by about $72,000 from other Knoxville sources. A former farmer, Shields was associated not just with banks, but with multiple industries—and with managing the political career of his brother John K. Shields, who was then a U.S. senator.

For the elusive field, the group identified seven acres to the south of campus near the river, and along the western bank of Second Creek: a low floodplain that contained small houses and various other structures.

In gratitude, Young first suggested it be named Shields Field. Perhaps in the interest of something more euphonious, they finally chose to include Shields’ wife in the name. It was her money, too. Chattanooga native Alice Watkins, who had married Shields back in 1889, became the co-honoree.

However, it’s hard to say that Shields was a bigger contributor than Dr. Charles E. Ferris, dean of engineering, and a big football fan, who lived on White Avenue, so close to Wait Field that an errant punt might land in his yard. Born in Ohio during the Civil War, Ferris had a doctorate from Johns Hopkins and became notable on the Hill for his expertise in electricity and his luxuriant mustache. He had never played football in his life until he arrived at UT in 1892, and found himself “drafted” to serve as a lineman on UT’s first football team to play a full season. In those days, even 28-year-old professors were allowed to represent the Vols on the gridiron. His Vols played on Baldwin Field, near Western Avenue. He became a football fan.

To this project, Ferris donated more time and expertise than money. Ferris had been part of that original effort in 1912, and in 1919-1921, he was the acting chief contractor of the project, volunteering to direct the grading of the field, and erecting the first concrete bleachers.

Making hilly land perfectly flat is hard to do, especially when there are houses on it. They bought the parcels, sent the residents packing, demolished the houses, and went to work flattening the land. As they got into the real work of it, it became clear that building a perfect football field was going to take much longer than the three months originally budgeted.

UT President Brown Ayres, one of the original charter supporters, died weeks before the announcement of Shields’s gift. He was succeeded by Canadian-born entomologist Harcourt Morgan, who saw it through.

|

|

Shields-Watkins Field courtesy University of Tennessee |

It was a community effort. In the spring of 1920, students and faculty members were asked to volunteer their time to help Ferris with the complex leveling project—appealing for help also to alumni “who can arrange to be a schoolboy once more.” But supporters weren’t all UT alumni. One of the major donors was Major E.C. Camp, the Union veteran, and industrialist who was from central Ohio. Shields himself, the single biggest donor, was not even a college graduate. Like Ayres, Camp died months before their beloved project was completed.

There were plans to have it finished by Oct. 9, 1920, for the big game with Vanderbilt, for which Wait Field was not considered adequate either as a gridiron or as a venue big enough for the crowd. That would be the equivalent of a grand opening.

It was a big day for Shields-Watkins, just not that they hoped. It wasn’t ready for football. President Morgan said people could park their cars there on the new field, and they’d playback on Wait Field. It was a welcome option because there wasn’t enough parking on the Hill for a game day.

They fell back, hoping Shields-Watkins would be done in time for the Kentucky game, at Thanksgiving. It wasn’t quite for that, either, but it played another role. It was the destination of a 3.7-mile Thanksgiving Day competitive run, starting at Cherokee Country Club.

The concrete bleachers were the last part of the project to be completed. They sometimes called it a “stadium,” but the bleachers were just simple stands, on only one side of the field. Holding 3,200, they were big, but in pictures, the field doesn’t look much bigger than a typical high-school football field.

The first games ever played on Shields-Watkins field were baseball games, the following spring—interspersed with track meets.

But football was what folks had in mind when they planned the field. Shields-Watkins got its football initiation on Sept. 14, 1921, when the UT Vols—led by Coach M.B. Banks, a New York-born Syracuse alum, beat Emory & Henry, 27-0. It was a good year for the Vols, who won all five of their first home games on the new field, against Maryville, Chattanooga, Florida, and Sewanee (don’t laugh—Sewanee beat Alabama that year). They finished their first Shields-Watkins season with a winning record of 6-2-1.

|

|

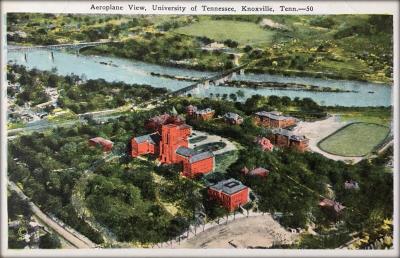

Postcard aerial view courtesy of KHP |

At that time, no one named Neyland lived in Knoxville. Coach Robert Neyland, an army officer from West Point who had some unusual ideas about football--arrived in town about four years after the completion of Shields-Watkins Field. But as coach of the Vols beginning in 1926, he made good use of it for a quarter-century and saw its seating swell from 3,200 to almost 50,000. The ever-growing stadium was named for the brigadier general shortly before his death in 1962. But all the while, it was the same field, which in the last century has seen several hundred football games, witnessed a few national championships, drawn literally millions of fans, and endured the cleats of several of the most famous football players in history.

Postcard aerial view courtesy of KHP

The original idea that a good football field would raise the university’s profile may have been valid. UT built something else, simultaneously, that did the same thing in a very different way. Under construction on a similar schedule, and completed at about the same time, was a monumental building on the very top of the old Hill, to be known as Ayres Hall. It had stone arches and a bell tower and even gargoyles and was hard to miss. The tower had an unusual checkboard pattern, a Chicago architect’s flourish. Years later, that checkerboard would be echoed in orange and white on Shields-Watkins Field, where Ayres Hall was prominently visible from the stands. UT’s distinctive checkerboard end zone also reflects something added to the campus in 1921.

For UT, something worked. Over the next dozen years, the university’s enrollment quadrupled, and the campus was, really for the first time, coming to seem a familiar part of Knoxville.

-

2021 Marks 100 Years at Neyland

2021 Marks 100 Years at Neyland

From a 3,200-seat concrete grandstand in 1921 to today's college football coliseum. The venerable Neyland Stadium turns 100 this season.

From a 3,200-seat concrete grandstand in 1921 to today's college football coliseum. The venerable...

Looking to go to a University of Tennessee Football Game? Check out our Guide to Gameday!

Get to know this part of town with our In the Neighborhood: UT & Campus Guide!