Knoxville has worn lots of hats over the years, from “The Marble City” to “Gateway to the Smokies” to “Home of the Vols.”

However, many people around the world don’t even know what American football is, much less that we play it here--but they’ve heard of Knoxville, anyway. They know us for our literature. For whatever reason, we seem to have at least a little more than our share of it.

The single writer most associated with Knoxville may be James Agee (1909-1955), whose best-known works are Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and A Death in the Family. The latter is his autobiographical novel concerning the sudden car-accident death of his own father, and is set in Knoxville, in 1915-1916. It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1957 upon its publication after Agee’s own death, and has been in print ever since, inspiring an award-winning Broadway show, All the Way Home, as well as four different motion pictures, including a big-screen feature starring Robert Preston and Jean Simmons, and a Masterpiece Theatre production starring John Slattery and Annabeth Gish. (Actually, there are five if you count an extremely eccentric Swiss director’s pseudo-documentarian take on it in 2019.)

The single writer most associated with Knoxville may be James Agee (1909-1955), whose best-known works are Let Us Now Praise Famous Men and A Death in the Family. The latter is his autobiographical novel concerning the sudden car-accident death of his own father, and is set in Knoxville, in 1915-1916. It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1957 upon its publication after Agee’s own death, and has been in print ever since, inspiring an award-winning Broadway show, All the Way Home, as well as four different motion pictures, including a big-screen feature starring Robert Preston and Jean Simmons, and a Masterpiece Theatre production starring John Slattery and Annabeth Gish. (Actually, there are five if you count an extremely eccentric Swiss director’s pseudo-documentarian take on it in 2019.)

The original book’s “prologue,” actually a separate nonfiction piece well known on its own for years before the novel was published, was “Knoxville: Summer 1915.” It inspired a soprano piece by one of America’s most famous composers, Samuel Barber, who had already been inspired by other Agee works. It’s performed so often around the world that it’s safe to say that most who sing and play and hear it have never been to Knoxville—although its imagery of noisy streetcars and “locusts”—we call them cicadas now—is vivid and specific.

Agee’s home, described in that piece, was in the Fort Sanders area, on the 1500 block of Highland Avenue, now a neighborhood noisy with undergraduates. Agee Park, at the corner of James Agee Street and Laurel Avenue, is inspired by his legacy, and on some rare occasions has inspired Agee-related events. Although Agee’s home was torn down almost 60 years ago—ironically, during the production of the first movie version of All the Way Home, filmed in the same neighborhood—most of the neighboring houses are still there, and if you squint your eyes on a hot day, maybe you can picture it.

Agee’s home, described in that piece, was in the Fort Sanders area, on the 1500 block of Highland Avenue, now a neighborhood noisy with undergraduates. Agee Park, at the corner of James Agee Street and Laurel Avenue, is inspired by his legacy, and on some rare occasions has inspired Agee-related events. Although Agee’s home was torn down almost 60 years ago—ironically, during the production of the first movie version of All the Way Home, filmed in the same neighborhood—most of the neighboring houses are still there, and if you squint your eyes on a hot day, maybe you can picture it.

Agee's birthday, by the way, is Nov. 27. Some fans do celebrate it, with a reading or a drink. He would have been 112 this year. Astonishingly, considering what he produced in his lifetime, from the screenplay for The African Queen to the landmark of new journalism, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, he died of a heart attack at age 45.

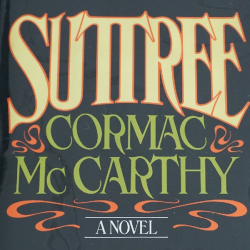

Perhaps more famous than James Agee today is Cormac McCarthy (1933- ), who’s known for his visceral and often violent stories of the West. However, he grew up in Knoxville, attended UT, and wrote his first several novels while he lived here. Two of his novels, his first, The Orchard Keeper, and his fourth, Suttree, have very specific Knoxville settings. McCarthy, who combines gritty, hyperrealistic and sometimes horrific situations with almost elegantly poetic prose, is probably not for every taste, but his books have sold in the millions and inspired several major motion pictures, including All the Pretty Horses and No Country for Old Men—as well as The Road, his novel that won the Pulitzer Prize. That book, unusual among his novels, is set in a post-apocalyptic landscape without place names, but one early scene is quickly recognizable to locals as a vision of a ruined Knoxville.

Unfortunately, the country house where McCarthy grew up and began writing burned down not long after he won the Pulitzer—it was south of town, on Martin Mill Pike—but many of the scenes of Suttree, which is set downtown in 1951, are recognizable today. Market Square, in particular, is elaborately described in both Suttree and The Orchard Keeper, which is set in the 1940s. Suttree has a bit of a cult following, and fans from as far away as Australia have come to Knoxville to see if it’s just possible there’s a real place like “this obscure and prismatic city,” as McCarthy described it. Suttree’s bar, just around the corner from Market Square on Gay Street, is inspired by that novel, as is the city park known as Suttree Landing, on the South Knoxville riverfront.

Unfortunately, the country house where McCarthy grew up and began writing burned down not long after he won the Pulitzer—it was south of town, on Martin Mill Pike—but many of the scenes of Suttree, which is set downtown in 1951, are recognizable today. Market Square, in particular, is elaborately described in both Suttree and The Orchard Keeper, which is set in the 1940s. Suttree has a bit of a cult following, and fans from as far away as Australia have come to Knoxville to see if it’s just possible there’s a real place like “this obscure and prismatic city,” as McCarthy described it. Suttree’s bar, just around the corner from Market Square on Gay Street, is inspired by that novel, as is the city park known as Suttree Landing, on the South Knoxville riverfront.

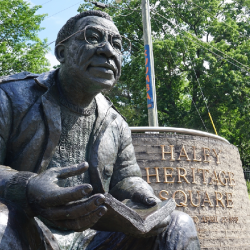

Of course, Roots author Alex Haley lived in and near Knoxville between 1984 and his death in 1992. While he was here, the West Tennessee-born Haley wrote mostly magazine pieces. He said he was working on an East Tennessee novel, but it has never come to light. He liked people, though, and gave dozens of public talks at the university and elsewhere. A community effort resulted in an enormous bronze statue of Haley, at Haley Heritage Square, just east of downtown on Dandridge Avenue. It’s one of the largest statues of a writer in America.

But Knoxville’s literary reputation is not a very new thing. Over 150 years ago, one of the most controversial and popular books in America was Sut Lovingood’s Yarns, by George Washington Harris (1814-1869), who spent began his writing career during the 30-odd years in Knoxville. He moved away during the Civil War, but by a bizarre coincidence happened to be passing through here on the train when he died in 1869. He was living here as a businessman, local postmaster, Presbyterian elder, and occasional contributor to New York magazines when he began writing his Sut stories in the 1850s, in which he described a thoroughly uncivilized and often blasphemous mountain kid that resonated with readers across the country, including Mark Twain, who was living in San Francisco when he discovered Harris’s work. Later, both William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor have cited Harris as an influence. Unfortunately, his Knoxville has almost entirely vanished, though a few members of his family are buried at First Presbyterian’s churchyard, and he was almost certainly familiar with the saloon that occupied the space now known as the Bistro at the Bijou.

But Knoxville’s literary reputation is not a very new thing. Over 150 years ago, one of the most controversial and popular books in America was Sut Lovingood’s Yarns, by George Washington Harris (1814-1869), who spent began his writing career during the 30-odd years in Knoxville. He moved away during the Civil War, but by a bizarre coincidence happened to be passing through here on the train when he died in 1869. He was living here as a businessman, local postmaster, Presbyterian elder, and occasional contributor to New York magazines when he began writing his Sut stories in the 1850s, in which he described a thoroughly uncivilized and often blasphemous mountain kid that resonated with readers across the country, including Mark Twain, who was living in San Francisco when he discovered Harris’s work. Later, both William Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor have cited Harris as an influence. Unfortunately, his Knoxville has almost entirely vanished, though a few members of his family are buried at First Presbyterian’s churchyard, and he was almost certainly familiar with the saloon that occupied the space now known as the Bistro at the Bijou.

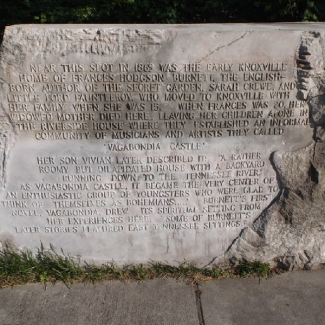

If Harris had an opposite in Victorian-era fiction, it was Frances Hodgson Burnett, the prolific English-born novelist who described her mostly well-bred characters with subtlety and grace. Best known today for The Secret Garden, The Little Princess, and Little Lord Fauntleroy, Burnett (1849-1924) wrote dozens of popular books that have been made into more than 60 movies since the dawn of silents.

She was about 15 when her struggling family moved here from Manchester and began her career as a writer when the Hodgsons lived in a tiny house she called “Noah’s Ark” in what’s now Mechanicsville, and helped support her widowed mother and several brothers and sisters with her short stories, which were mostly comedies of manners. Many of her books are set in England; one of her first was Vagabondia, set in London, though her son claimed that it was based on her memories of life and people in Knoxville. Some of her more obscure fiction, including a long out-of-print novel and a few stories have disguised Knoxville settings, and her eccentrically allegorical memoir, The One I Knew the Best of All, describes her early days here and her beginnings as a writer.

Her several houses have long since vanished, but the grave of her mother—Eliza Boond Hodgson, who died in 1870--is still there right by the lane in the southern part of Old Gray Cemetery. And in recent years, there’s a creative homage to her in the Knoxville Botanical Gardens, a “secret garden,” with playful allusions to Burnett’s most-filmed novel.

Knoxville has family connections to playwright Tennessee Williams, whose father grew up here, and after a disappointing personal life, died here. Williams used a few Knoxville allusions in some of his plays—notably Suddenly Last Summer. Although set in Louisiana, the name of a dreaded mental institution is “Lion’s View”—it can be no coincidence that the address and familiar name of Knoxville’s mental institution was “Lyons View.” Now the site of Lakeshore Park, the original central building still stands. His father, grandparents, and several other family members are buried at Old Gray, perhaps appropriately just a few steps from Broadway.

Landmark philosopher, critic, and environmentalist Joseph Wood Krutch (1893-1970) grew up in Knoxville and graduated from UT and is remembered in quotations inscribed in the pavement of the downtown greenspace established by his brother, Charles: Krutch Park.

Two other novelists almost exactly Cormac McCarthy’s age have both used Knoxville in their work: David Madden (1933- ), whose 1974 novel Bijou, set in a somewhat altered Knoxville (called “Cherokee” in the book), earned national attention, including a generous shout-out from Stephen King. Richard Marius (1933-1999), the legendary UT professor (later Harvard professor) who wrote a series of novels set in the Knoxville area that also earned national reviews, including The Coming of Rain, which is set in post-Civil War Loudon County, and An Affair of Honor, which is partly set in a suburbanizing Knoxville.

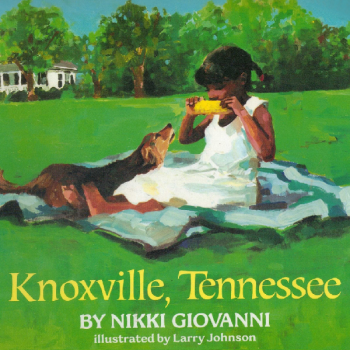

Born in 1943, Nikki Giovanni, first known for her strident poetic contributions to the Black Power movement, was born and partly raised in Knoxville. A plaque stands near her beloved grandmother’s home on Hall of Fame Drive, an address she described in a well-known autobiographical essay called 400 Mulvaney Street. Her short poem, Knoxville, Tennessee, an uncustomarily nostalgic memoir of family, food, and other things from her early childhood, surprisingly re-emerged as the text for a colorful children’s book in the 1990s. It’s quoted in marble at Volunteer Landing. She visits frequently and has spoken here on many occasions.

Born in 1943, Nikki Giovanni, first known for her strident poetic contributions to the Black Power movement, was born and partly raised in Knoxville. A plaque stands near her beloved grandmother’s home on Hall of Fame Drive, an address she described in a well-known autobiographical essay called 400 Mulvaney Street. Her short poem, Knoxville, Tennessee, an uncustomarily nostalgic memoir of family, food, and other things from her early childhood, surprisingly re-emerged as the text for a colorful children’s book in the 1990s. It’s quoted in marble at Volunteer Landing. She visits frequently and has spoken here on many occasions.

Nephew of a notable football coach, Inman Majors has written several fictionalized versions of real situations, including his football-famous family (Love’s Winning Plays) and the Butcher brothers of World’s Fair fame (The Millionaires).

Richard Yancey’s unusual career has led him from IRS agent to popular writer of young-adult fantasy fiction (one of which became a major motion picture), lived in Knoxville for many years, and set his “Highly Effective Detective” series of pseudo-noir mysteries here, mostly in and around downtown.

And UT’s unusual forensic laboratory has been the focus of several mystery novels, beginning with Patricia Cornwell’s The Body Farm, and followed by the pseudonymous Jefferson Bass’s “Body Farm” series.

Some of these legacies, especially those of Agee and McCarthy, have spawned multi-day academic conferences, concert series, and marathon pub crawls—as well as inscriptions in Market Square’s pavement and in stones along Volunteer Landing—and in the name of a public park called Suttree Landing.

You can learn more about these locations in the Knoxville History Project’s illustrated book, Historic Knoxville: The Curious Visitors’ Guide.