Knoxville has an industrial history, but never relied on just one product. From its mid-19th-century origins, the city’s industrial base was very diverse. We made nearly everything here.

The phrase “the Marble City,” was first coined to describe Knoxville’s distinctive marble and limestone products in the 1880s. Lumber, coal, iron, and machinery of various sorts were produced here for many years, along with several packing houses, a durable coffee roaster, and a flour mill that made the brand White Lily famous. But the city was also sometimes known as “the Underwear Capital of the World.”

May 3 is National Textile Day. Although several of Knoxville’s old textile mills are lost without a trace, there’s enough left for an offbeat textile-industry-history tour of town.

It may seem surprising, considering Knoxville’s distance from the Deep South’s cotton belt, that the city hosted an array of textile mills, some of them major mills even on a national scale. Cotton’s very scarce in East Tennessee, but Knoxville’s railroad connections and ready workforce made it attractive to textile-manufacturing interests. By 1930, Knoxville boasted 22 textile and clothing factories, employing 8,000 people, claiming to be, most specifically, “the largest heavy-weight cotton-knit underwear manufacturing center in the world.”

By 1935, the city was boasting of being “the underwear center of the United States.” Knoxville made T-shirts, socks, stockings, shorts, jock straps, and women’s lingerie—but also overalls, gloves, canvas tents, seatbelt straps, felt hats, blue jeans. It all started several years after the Civil War.

Much of the Old City area was textile-related, especially the buildings on the south side of West Jackson, which a century ago formed a miniature garment district, with factories and wholesalers dealing in shoes, hats, and suits. Some of it remained into recent years; John H. Daniel, a custom suit manufacturer, moved to a new location at 1803 North Central in 2014, and its original big old brick building—now known as the Daniel—was converted to luxury residential.

Brookside Mills

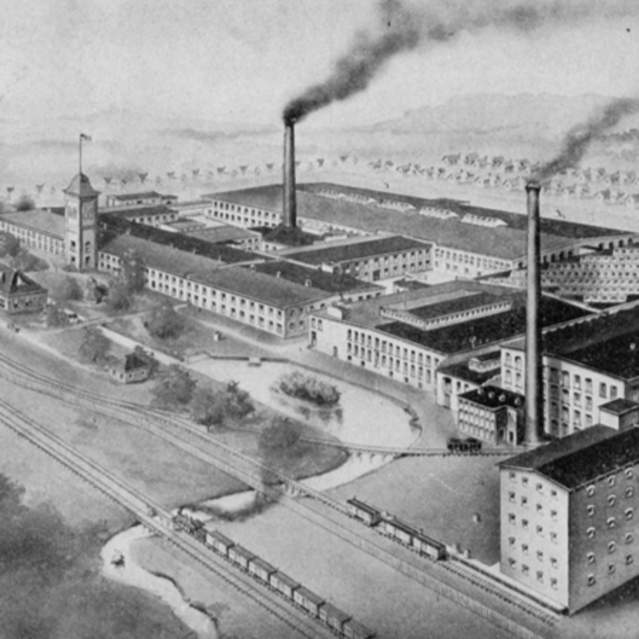

Brookside Mills wasn’t the very first textile mill in town, but it was very early, and proved to be durable. Established in 1885, it lasted until 1956, and was one of Knoxville’s largest and proudest businesses, a model mill with interior garden courtyards and a day-care program for its 1,000-plus employees. Brookside was a weaving mill, as opposed to a knitting mill, a distinction its employees were quick to boast about, because the process involved an extra later of complexity and skill in the textile business.

It had its dark side, by modern standards. It was typical for children to work in textile mills, and in 1910, progressive photographer Lewis Hine documented Knoxville children coming and going to work. A 1902 state law banning child labor was never effectively enforced, and child labor in Knoxville’s factories may not have ended until sweeping federal legislation in 1938.

Little of Brookside Mills remains, notably one long, two-story brick building along the 500 block of Baxter Avenue with the faded sign reading “The Mill Outlet.” Most of the factory was demolished. However, Brookside thrived in an era when all its employees, including management, lived within walking distance, and developed its own commercial center. The semi-urban area built for groceries, bars, pool halls, hardware stores, clothing stores for the concentration of population around Brookside Mills are now known as Happy Holler. It became a sort of “mill town” of its own, although it was within city-limits Knoxville, and walking distance of downtown. Happy Holler is one of Knoxville’s most popular destinations today, but probably wouldn’t be there if not for the legacy of the big weaving factory that closed almost 70 years ago. (Visitors today can catch a cult classic film at Central Cinema, shop yesteryear at Retrospect Vintage and Raven Records, enjoy dining from pizza and beer at Central Flats & Taps or fine dining at Bistro by the Tracks. Several other neighborhood haunts include the Original Freezo for soft serve, Remedy Coffee and adjacent Paysan, Three Rivers Market, and more.)

That area has a connection to Hollywood. Brookside’s success is what drew mill-management specialist Larkin Brown from Massachusetts around 1900. Becoming manager of Brookside, Brown brought his family, including son Clarence Brown, the future Hollywood director. The future director of Anna Christie, The Human Comedy, and National Velvet grew up around Happy Holler and studied his dad’s factory as part of his engineering studies at UT. (Visitors today can enjoy the professional theatre named his honor, the Clarence Brown Theatre on the University of Tennessee’s campus.)

***

One old textile mill still stands downtown, although it has not served that purpose in more than a century. Now mostly a residential building, the Cal Johnson building was built in 1898 to be a factory to produce work clothes like overalls. It served that purpose for only a few years, later adapted as a car dealership and later still a warehouse. What makes it remarkable is that it was built by a man who was raised in slavery. Cal Johnson, who lived with his wife in a house next door, was an exceptional businessman who somehow overcame racism in the early Jim Crow era to succeed in a segregated city. His name, “Calvin F. Johnson,” is still engraved high on the front of the building. Find it at 301 State Street, parallel to Gay Street.

Standard Mill

Once a very large plant that produced literally millions of garments annually for a national and international market, Standard Knitting Mill, which closed in the 1990s after nearly a century of production, has been reduced by demolitions and a recent fire. What remains is little more than half of the original complex. Standard Knitting Mill, which became known for underwear sold in every state in America, was the South’s biggest underwear producer.

Standard was, among many other things, one of the nation’s leaders in supplying a new demand when sometime in the late 1960s, Americans started wearing print T-shirts—not just as undershirts, but on the outside—with colorful prints of Mickey Mouse or the “Keep On Truckin’” guy. Standard made those trademark tees here.

It’s been claimed that Standard produced more than one million undergarments per week. Although the neighborhoods around it, namely Parkridge, are busy with new residents now, the old factory is quiet.

What remains is clearly visible from the other side at Caswell Park. Now used mostly for community softball, Caswell Park served for almost 80 years as Knoxville’s pro-baseball stadium, and home plate was so close to Standard that long foul balls broke out dozens of the factory’s hundreds of high windows. The large brick structure has been the subject of several plans in recent years, but at this writing, its fate is uncertain.

Adjacent to the old mill, though, visible and accessible from 6th Avenue, is a renovated industrial building now home to Patricia Nash’s international handbag company; one could claim she continues some of the fashion-accessories tradition of Knoxville’s textile industry.

The little “downtown” section of 1500 Washington Avenue, which shows some signs of reviving, was a cluster of stores that grew there a century ago to serve Standard’s many employees. (Today visitors can find a large mural inspired by the poetry of Jimmy Carter and the beauty of East Tennessee, lowercase books - a used bookshop, and The Flower Pot Galleria and Eatery – a combination florist and café, and other businesses.)

Holston Mills

More obscure is the Holston Mills, farther to the northeast of Standard, on the other side of I-40. It’s the big, hulking gray concrete building on Ninth Avenue just north of Mitchell. It was known for manufacturing hosiery, which is what it did here for almost 60 years, until it closed in 1979. Its attractively stylish but commanding ca. 1920 concrete building is still intact, used in recent years as a warehouse.

Women often had difficulty getting jobs in Knoxville except as domestic servants or stenographers. Most heavy-industry factories hired only men. But because women were perceived to have a knack for sewing and knitting, several textile mills hired women in larger number than men.

Ca. 1918 Cherokee Mills is close to the well-trafficked center of town, on Sutherland Avenue at the corner of Concord, northwest of UT campus. It manufactured cotton yarn. Most of its employees were women, who went on strike in 1934, partly because of inadequate women’s-room facilities. That Cherokee strike was featured in a PBS documentary about women leaders in the labor movement. It was one of the most dramatic strikes in Knoxville history.

Cherokee remained in business here until 1955, when its owner, complaining about Knoxville’s high taxes, moved it into a more modern facility in Sevier County.

After it closed, its building housed a potato-chip factory for several years, but artfully restored with lush landscaping, the building might easily be mistaken for new. It now offers medical and tech-oriented business space. If you drink a cup of coffee at The Golden Roast, the locally well-known coffee shop at the western end of the building, you’re visiting Knoxville’s textile (and labor) history.

***

Several textile mills, even large ones, are gone without a trace. Palatial Knoxville Woolen Mills, later known as Appalachian Mills, which stood north of Fort Sanders near I-40, was still a very large and interesting ruin as late as the 1970s, but it’s hard to find any trace of it today. Jefferson Woolen Mills, on the south side of the river on Blount Avenue, was torn down in more recent years.

Like a lot of industries, Knoxville factories suffered from foreign competition—as well as competition from rural counties offering cheaper tax rates for industry. Bucking a downward trend, Levi Strauss opened a Knoxville plant in 1953, just as some other old-line textile mills were closing or moving away. The Cherry Street plant proved to be a major exception to the textile trends, employing as many as 2,300 and manufacturing as many as 7,000 pairs of jeans per day, and became the biggest Levis producer in America. But foreign competition and high-fashion jeans contributed to its decline and closure in 2002. Its long, low, modern-style building might seem nondescript from the street until you realize how big it is. It survives in East Knoxville, on the east side of Cherry Street between I-40 and Cecil Avenue, and has been used for a variety of purposes, from law enforcement to furniture storage.

There are still a wide variety of boutique and specialty fabric and clothing producers in Knoxville today that may count themselves as a legacy of Knoxville’s Underwear Capital days. But the textile business may have one very surprising legacy. It played a role in bringing a once-obscure tree out into the open.

Dogwoods are native to East Tennessee. But for decades, they lived mainly in the mountains, noticed by hunters when they bloomed in the spring, but our ancestors saw little value in them as ornamental trees in yards and gardens. Oaks, elms, and walnuts were seen as perfect trees, tall, straight, and symmetrical, the trees people liked to see in their yards and lining their streets. Dogwoods were crooked, never got very big, and their bark flaked off; some folklore suggested they were cursed. However, the textile industry valued dogwoods. Their wood was very hard and durable and especially useful in the textile industry, because it was the best wood for spindles, the essential parts in all textile mills. Dogwoods were grown just to harvest their good wood. By the 1920s, people seemed to begin noticing how pretty a dogwood might be in a suburban yard in the springtime.

(The dogwood is iconic in East Tennessee. Learn more about the beauty of this area alongside arts and culture promoted through annual events and programming by local organization Dogwood Arts.)