|

|

Kingston Pike Postcard | Courtesy Knoxville History Project |

Sunday, January 17, is National Bootleggers' Day, believe it or not. Knoxville didn't start that holiday, which is just five years old now, but our city has quite a rich story in that regard. Knoxville and liquor go way back, of course. Distilling was one of Knoxville's first industries. Young men would load local whiskey onto flatboats, then make the month-long trip downriver to New Orleans and sell it for a fortune.

Later, at the turn-of-the-century height of the saloon era, the city supported 106 competing saloons and a big brewery. All that came to an end in 1907, when a referendum started Prohibition here 12 years before it caught on nationwide, by way of the 18th amendment. But in surprising ways, it started a whole new era that we now remember with something like nostalgia.

That 12 years gave Knoxville's bootleggers a lot of practice, and a head start. It may be thanks to Knoxville's early jump on Prohibition that the city became a bootleg-whiskey clearing house not just for the region, but for much of the nation. Bootlegging was a term that became popular nationally in the 1880s, a term probably referring to one effective way to hide a flask of whiskey, in a boot leg.

As odd as it may seem, when bootlegging was mentioned in Knoxville papers in the late 19th century, it was always about something that existed far away, mainly in communities in the Midwest that were experimenting with banning alcoholic beverages. Knoxville didn't have many limits on what saloons could serve—and therefore had no market for bootleggers. But Temperance Fever hit Knoxville in the early 20th century, and an industry was born. After city voters banned Knoxville's saloons in 1907, and new state laws restricted manufacture of alcoholic beverages in 1909, the demand remained, and bootleggers learned to maintain a supply by illegal routes. As Prohibition gained strength nationally, Knoxville bootleggers were developing networks that may have put us a few years ahead of the rest of the country.

One of Knoxville's advantages in that regard was its proximity to the Smoky and Cumberland Mountains, where small farmers grew corn in hidden hollers remote from law-enforcement authorities. Manufactured in hundreds of miniature distilleries—stills, for short--moonshine became a common term, for the first time, and familiar even down in the cities. It was so named, of course, because it was often made at night, by the light of the moon, it was known as “moonshine.” (The word was already in the language, but usually referred to nonsense.) The term “mountain dew” became more popular during Prohibition, with a new song called “That Good Old Mountain Dew,” written by offbeat attorney/folklorist Bascom Lamar Lunsford—he lived less than 100 miles east of Knoxville.

|

|

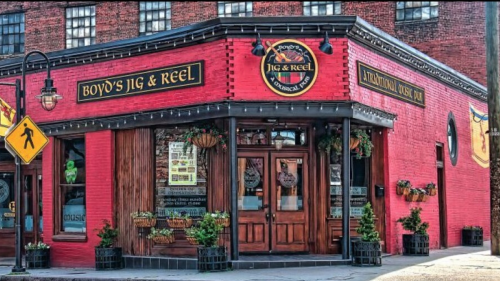

Boyd’s Jig and Reel in the Old City |

Most Knoxvillians had probably never tasted corn liquor before, but because it was more available than Scotch, it became a thing. (If Scotch is your preference, head to Boyd’s Jig & Reel where they have over 800 selections of Scotch whisky, one of the largest in the world.)

In 1919, Tennessee was one of the states that joined the majority making alcohol production and distribution illegal all across the United States. Knoxville was already there, and had liquor production and distribution machines in operation. By the 1920s, East Tennessee moonshine was not just for local consumption. Stories about gangster Al Capone having interests in Knoxville are hard to prove, but impossible to disprove; there was definitely moonshine served in the many speakeasies of Chicago. When Scripps-Howard columnist Ernie Pyle wrote a story about the moonshine industry of East Tennessee, he remarked that Knoxville served as its national distribution center.

The city retained that status even after national prohibition lifted in 1933, when a market for moonshine remained robust for years after the tamer whiskeys were easily available across the nation.

If not in Knoxville. Prohibition was national for only 14 years, but in Knoxville, liquor by the bottle—wine, even--remained illegal here until 1961. Religious moralists liked it that way, and so, of course, did the bootleggers. Many city bootleggers did their job quietly, and were much appreciated by country clubs, nightclubs, and wedding planners. Many of them were people who may have had a day job, but made some extra money delivering illegal liquor and beer to speakeasies and as well as private homes. Bootleggers existed co-equally in the white and African American communities; one famous Black bootlegger named Freddy Logan was a publicly prominent concert promoter. Beardenites still talk about Dick Vance, a postwar bootlegger who had a drive-in location off Sutherland Avenue.

Some of their product was legally manufactured liquor smuggled in from states and countries. They also trafficked in moonshine. They minimized interference from authorities by locating just outside of city limits—or making friends with law-enforcement officials, perhaps with special favors.

Others were more competitive; rather than make friends with the police, a few legendary figures just tried to be faster than the police. It's well known, and often related, how bootleggers in souped-up stock cars were so proud of their skills behind the wheel that they began racing each other, creating the new sport. What defines NASCAR is not that they're the fastest cars on the planet, but that they're the fastest cars that look deceptively like regular cars—borrowing some tricks from the bootleggers who were some of the first stock-car champions.

|

|

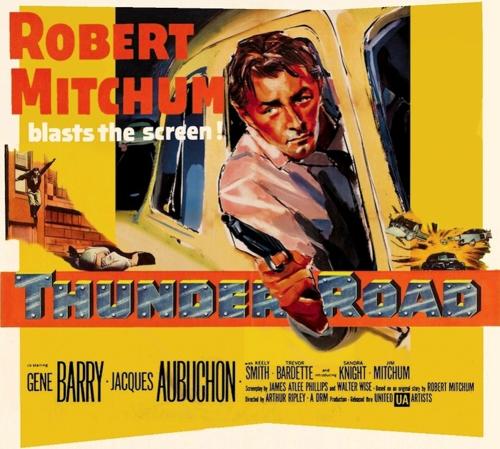

Thunder Road Film Poster |

The bootlegging culture attracted Hollywood actor/writer Robert Mitchum, who in 1958 created the most talked-about movie in East Tennessee history, Thunder Road. It was a story of a bootlegger named Luke Doolin. In the movie, Knoxville is mentioned a few times. This city was neither a setting (that was East Kentucky and Memphis) nor a shooting location (that was Asheville and Western North Carolina)--but the song that promoted the movie, Mitchum's own “The Ballad of Thunder Road,” which became a national hit and likely better known than the movie, is very specifically set in Knoxville. He describes a high-speed bootlegger with the authorities in hot pursuit: “Blazin' right through Knoxville, out on Kingston Pike / Then right outside of Bearden they made the fatal strike.” The specifics of the song, and some mystery about whether the ballad is based on a real event—there are several possible Knoxville-area inspirations to pick from—have combined to inspire magazine articles, lectures, and whole books.

Bootlegging remained part of our culture. It's been claimed that Batman's Batmobile, introduced in 1941, was inspired by stories of souped-up bootleggermobiles with evasive gadgets.

As country music became more and more popular, “That Good Old Mountain Dew” was as much a standard as “Stella by Starlight” was in jazz. In 1959, months after “The Ballad of Thunder Road” hit the charts, the ill-fated songwriter known as the Big Bopper followed with his “White Lightnin'” which soon became a bigger hit for a little-known singer named George Jones. In 1988, Texas songwriter Steve Earle released “Copperhead Road,” probably his biggest hit. Almost a rock 'n' roll version of “The Ballad of Thunder Road,” it included the line, “He was headed down to Knoxville with his weekly load / You could smell the whiskey burnin' down Copperhead Road.”

The temperance people never knew what they started. There's still a romance to the bootlegging era, as attested by the reappearance of “speakeasies,” like the Peter Kern Library, a repackaging of moonshine as a legal drink, and the evocation of Thunder Road as both the name of a beer at Calhoun's on Kingston Pike and a cheeseburger at Litton's; they're miles apart, but both are on the trail Robert Mitchum described in his song.

Additionally, Tennessee Vacation offers its “White Lightnin' Tour,” a regional driving tour with 76 stops, several of them in downtown Knoxville. Not all of it is bootlegging related, but some of it does approximate the route of “Thunder Road.” The message seems to be that drinking's never been as much fun as it was when it was illegal. Maybe prohibition will come back around again. We already have the stills and speakeasies that made it memorable.

Looking for more places to sample some modern-day delights? Head to Knox Whiskey Works or PostModern Spirits, Knoxville’s two stops on the Tennessee Whiskey Trail. Cheers!