After 40 years, it’s still hard to believe it happened. Even those who don’t remember the 1982 World’s Fair – and at this point, most Americans weren’t even alive then – are obliged to know something about it. It’s the answer to “What’s that big golden thing standing on the west side of downtown?”

Fairgounds

Fairgounds

Gondola

Gondola

World's Fair Countdown

World's Fair Countdown

Only a few American cities have hosted officially sanctioned world’s fairs; Knoxville was one of the smallest American cities ever to attempt it (Spokane was about the same size as Knoxville when it hosted Expo ’74).

Energy Turns the World

Planned in the wake of the global Energy Crisis of the 1970s, Knoxville proponents cited the city’s status as the perfect city for a six-month celebration of energy. Knoxville is the headquarters of the Tennessee Valley Authority, the largest energy producer in the United States. It’s home of the University of Tennessee, known for energy research. And it’s near Oak Ridge National Laboratory, a major center for nuclear research. The idea was that the Knoxville International Energy Exposition, as it was formally known, would offer solutions to the apparent shortage of fossil fuels.

Construction of the World's Fair Site

The Fair was first proposed by retired Air Force colonel and downtown booster Stewart Evans during Mayor Kyle Testerman’s administration. It drew support from several of Testerman’s fellow Republicans, but banker Jake Butcher, a Democrat and sometime gubernatorial candidate, with the help of Democratic Mayor Randy Tyree, proved to be key to making the big event a success. The Fair’s biggest investor, Butcher became the most influential voice behind the planning of the exposition. But it would be an overtly bipartisan effort, as the Fair itself drew high-profile visits from both former President Jimmy Carter, who had made funds available for creating the Fair, and then-current President Ronald Reagan, who formally opened the Fair.

Participating nations involved some international drama. The Soviet Union had expressed strong interest, but Carter’s administration had withdrawn from the 1980 Moscow Olympics to protest the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Apparently in retaliation, the USSR withdrew from the Knoxville exposition.

The loss of that expected anchor of the Fair was a disappointment, but another nation once considered less likely than the Soviet Union may have proved a bigger draw. The traditionally reclusive People’s Republic of China was the biggest nation in the world but had never participated in any world’s fair. Under leader Deng Xiaoping, China was beginning to reconnect with the outside world, and creating a big pavilion in Knoxville seemed a way to symbolize its new openness. China’s participation in the 1982 World’s Fair was both the most popular aspect of the fair and, in retrospect, its greatest historical significance. China’s pavilion included a nod to energy technology, but was famous for its cultural museum, which included both live artisans and 2200-year-old terracotta warriors rarely seen outside of China.

Rubik's Cube

Another much more modest pavilion proved to be significant in retrospect. The European Economic Community exhibit – arranged as if it were another nation alongside the pavilions of France, Great Britain, Hungary, West Germany, and Italy – puzzled many fairgoers. It turned out to be the first World’s Fair pavilion for an organization that would later be famous as the European Union.

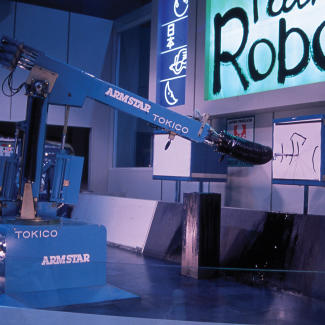

Painting Robot

Painting Robot

International Guests

International Guests

Dancing at the World's Fair

Dancing at the World's Fair

The international pavilions got the most attention. The Japanese pavilion was famous for its technological marvels, like Japan’s artistic robot and the viscerally realistic bullet train experience. Australia offered giant windmills and its Down Under Pub – down under the pavilion – where brawny blokes would sell you a cannister of Foster’s. Peru showed ancient Incan gold craft as well as a mysterious mummy. Mexico led visitors into a theater for a multi-sensory experience dramatizing the prehistoric origins of fossil fuels. Hundreds stormed the South Korea pavilion each morning to get a ticket to see the daily performances of its Korean dancers. The Saudi Arabia pavilion extolled the virtues of their king and an apparently unlimited supply of oil. Egypt’s pavilion was a museum of rarely seen artifacts of the age of the pharaohs. The Philippines featured a surprising creekside restaurant and a colorful bus powered by charcoal. And as you would expect, Canada’s pavilion was earnest, orderly, and low-key.

US Pavillion

The United States pavilion, in a large wedge-shaped hyper modernist building, demonstrated advances in energy research, but also something astonishing in 1982: a touch-screen computer. Most of the thousands who witnessed it had never even heard a rumor of such a thing and wouldn’t see anything like it for more than a decade to come.

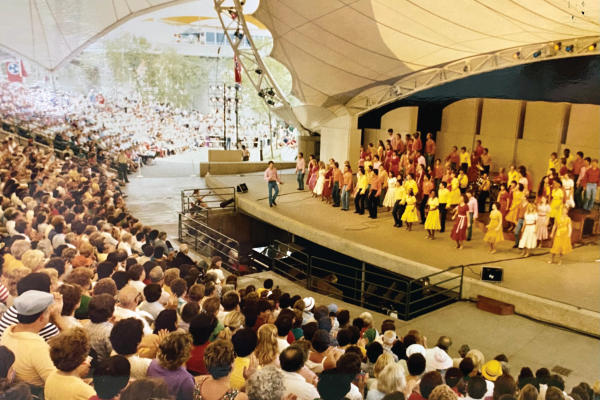

But beyond the national exhibits were hundreds of other attractions, technology exhibits, lectures, restaurants, and bars (memorably the Strohaus, where hundreds danced nightly to polka music), and a wide array of performances from legendary bluesman Brownie McGhee, Bob Hope, the young Ricky Skaggs, the Warsaw Philharmonic, and Japan’s Kabuki Theatre.

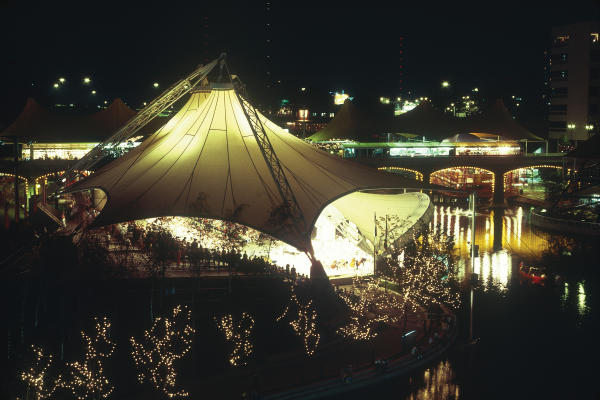

Tennessee Amphitheater Construction

Tennessee Amphitheater Construction

World's Fair Performance

World's Fair Performance

Several of those performances were at the Tennessee Amphitheater, an early creation by German designer Horst Berger, who has since become much more famous for his work on major buildings around the world, including the Hajj Terminal in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia; SeaWorld Pavilion in San Diego; Wimbledon Tennis Arena in London; and Denver International Airport – most of which bear a family resemblance to this one.

The Sunsphere

And there was that Sunsphere. It was an homage to the sun, the original source of all energy on Earth – though some preferred to compare it to a disco ball or a giant golf ball on a tee. All six months, there were lines to take the elevator up and see the world from inside it. Since 1982, the Sunsphere has served as an iconic feature of Knoxville’s skyline. It’s the only structure of its kind in the world. When one considers other structures created for other World’s Fairs – the Eiffel Tower (1889) and the Seattle Space Needle (1962) - its significance is apparent.

In all, the World’s Fair sold over 11 million tickets. It was, unexpectedly, America’s last successful international exposition. And it left us with one swell park and a lot of interesting memories.

Check out a list of upcoming activities celebrating the 40th anniversary of the 1982 World's Fair here.