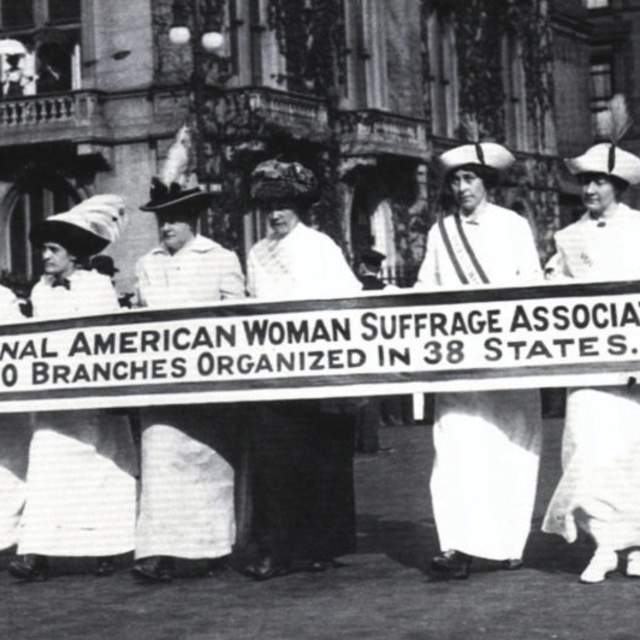

The suffragists must have felt the whole world was against them. When they arrived in Knoxville in late 1917, the band of courageous women were met with hostility. Nearly 70 years into the struggle for woman suffrage, the prize was in sight but still very far out of reach. More than a decade after Susan B. Anthony’s death, the finish of the battle had been left to a new generation.

Woman Suffrage had made it into the platforms of both national political parties, but President Wilson shirked any commitment to the movement by claiming he was not the leader of his party, but only the servant of his party, saying, “Ladies, you must concert public opinion on behalf of woman suffrage.” They were on their own and they went to work.

Tennessee Woman's Suffrage Memorial – this life size bronze statue commemorates Tennessee civil-rights pioneers Lizzie Crozier French, Anne Dallas Dudley, and Elizabeth Avery Meriwether.

Arrests and jailings did little to discourage the women. Former prisoners were sent on a Dixie Tour through the South in late 1917. Tennessee judges and lawyers formed committees that went to the owners of the halls, churches, private homes, local governments and even to the innkeepers across the state to convince them to refuse to accommodate the women or even break their contracts with them. The lawyers’ efforts were successful in most of the small towns and in Memphis and Nashville. In Knoxville, however, the lawyers met their match with the likes of Lizzie Crozier French and Maud Younger, who took to the stairs of the courthouse and addressed a crowd that stood shivering in the rain for more than an hour on a late November night. Those gathered learned of the common-sense fairness of the women’s requests and were shocked at the outrageous response of the government.

Knoxville survived the armed threats and clashes that November night and arguably set the example for other Tennessee towns. Just a little over a month later, in January 1918, Tennessee’s Congressman Thetus Sims switched sides and sponsored an effort to pass the Susan B. Anthony Amendment in the House of Representatives. After passage in Congress on June 4, 1919, there were 35 state ratifications by March 22, 1920, but the suffragists had to win at least 36 states.

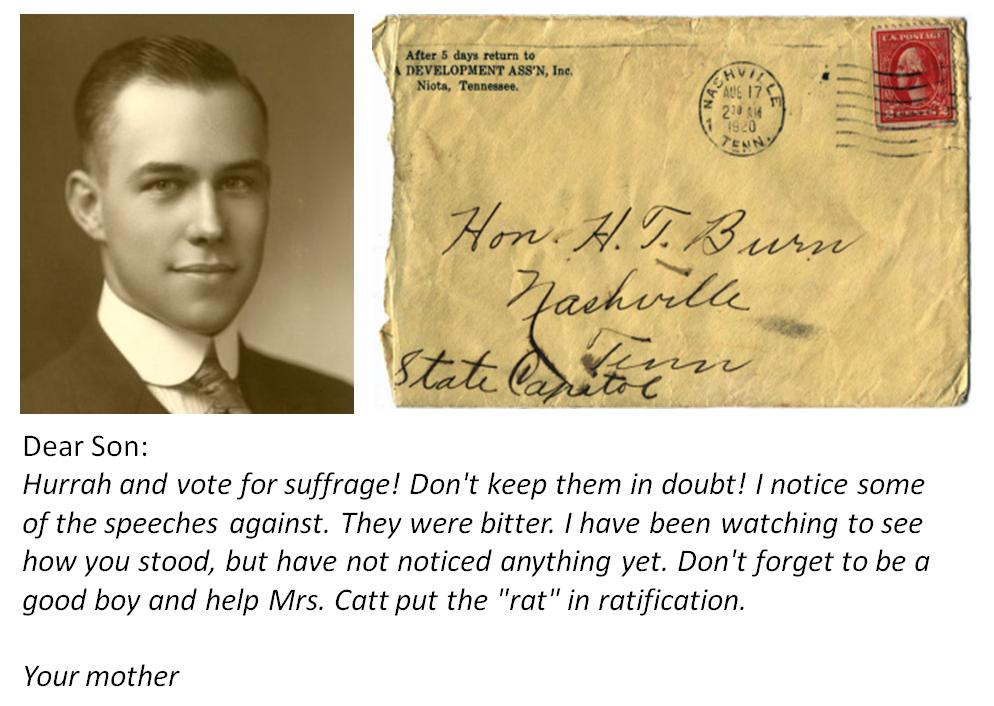

Burn Memorial – the statue depicts Rep. Harry Burn of Niota and his mother, Febb, and honors them for their roles in the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

The suffragists hoped Tennessee would become “The Perfect 36.” In the end, on August 18, 1920, a 24-year-old legislator from East Tennessee, Harry Burn, surprised the world with a last-minute switch of his vote from “anti” to in favor of ratification. Burn followed the advice of his mother, Febb Burn, and voted for the controversial measure. His vote broke a tie and Tennessee became the deciding ratification, granting all women the right to vote.

Febb’s letter to her son is on permanent display at the East Tennessee History Center

August 18, 2020 will mark the 100th Anniversary of the 19th amendment and the second official observation of Febb Burn Day. East Tennessee will celebrate with a variety of events.

This post was originally written in 2020 by Wand Sobieski. As founder of the Woman Suffrage Coalition, Ms. Sobieski is responsible for the women’s suffrage memorial statue that is featured prominently in downtown Knoxville’s Market Square and recognizes the women from Tennessee who played vital roles in securing the passage of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution giving women the right to vote.