This New Year's Eve, you'll probably drink some champagne, perhaps too much of it, and, come midnight, sing Auld Lang Syne, and perhaps kiss somebody. If you lived in Knoxville, say, 125 years ago, you probably did something else.

For Knoxville's first century or more, New Year's Eve and New Year's Day were considered just a lesser part of another holiday, called Christmas. Organizations often threw "Christmas parties," and "Christmas Dances," sometimes as late as the first days of January.

Christmas hadn't worn out its welcome, because people generally didn't start celebrating Christmas, or even decorating for it, until Christmas Eve. If Knoxvillians didn't strictly observe the "12 Days of Christmas," they gave it a couple of weeks, including New Year's, banishing the darkness with a series of parties and dances, almost every night. On Jan. 1, people were still greeting each other with “Merry Christmas.”

New Year's existed, though, and was an occasion for the newspaper editor to make another joke about learning to write the new year and reflect on the year triumphs and disappointments, and make projections, usually optimistic, about the year to come.

Cumberland Club Circa 1905 photo credit Shorpy.com

New Year's Day was a much bigger deal than New Year's Eve. New Year's Day was a holiday for formal visiting. Knoxville's wealthiest families, and some organizations, like the YMCA and the exclusive downtown men's club known as the Cumberland Club, might hold an Open House, usually in the afternoon. It wasn't just the house people came to see. Each Open House was always full of single young women. The purpose was to attract gentleman callers. There were toasts, but mainly with lemonade.

Gentlemen, of course, would leave their formal calling cards with the ladies. In 1880, the Strong store at 19 Market Square advertised their own Open House, too, but with a joke. “Callers with fine metal or greenback cards preferred.” Cash, in other words.

The phrase, “Ring out the old, ring in the new,” dates to the middle of the 1800s, and offers a hint about early American celebrations of New Year's Eve. At some point before 1880, churches greeted the new year at midnight by ringing their steeple bells. In 1899, according to the Journal, the most distinctive thing about the evening was the “peeling bells from every church tower at midnight. Their musical clangor sounded with strange distinctness at that still hour.”

Several local churches hosted “night watches” or "watch parties," when congregants, especially the young adults, would stay in the church until late, “ushering in the new year with a prayer.”

The tradition was more common in some denominations, especially Methodist and Lutheran. One church, the Pilgrim Congregational Church on West Vine, once associated with Swiss immigrants, hosted the annual banquet of the Pilgrim Literary Club. It's not obvious that it had a religious purpose. In the 1890s, the club's 18 members wore whimsical paper hats, each representing a different era of history, and were handed a literary quote they were to read to the group.

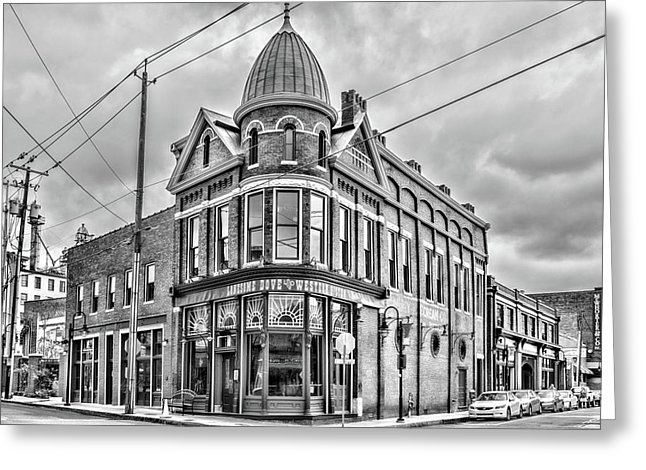

Modern Day Lonesome Dove (Historic Patrick Sullivan’s Saloon) photo credit Sharon Popek

It sounds as if there was a different story in the saloons. New Year's resolutions were a thing, even in the 1800s, and on Jan. 1 many young men made a go at giving up on drinking. On New Year's Day, 1888, a Knoxville saloonkeeper remarked that the first 10 days of the year were always his slowest, before all his customers gave up on their resolutions and began to drift back in. “The boys generally keep their oaths that long,” he said.

But for those who claimed to give up alcohol in the new year, New Year's Eve would be their last chance to guzzle without guilt. It offered an urgency comparable to Mardi Gras. So NYE's drinking tradition may have begun with would-be teetotalers, whether they were successful or not. By the turn of the century, it wasn't unusual for the police to pick up 50 for public drunkenness.

Church of the Immaculate Conception with Clock Tower courtesy of Knoxville History Project

When did people start celebrating in the streets at the stroke of midnight? It's hard to say, but reporters started writing about it in the 1890s. Before that, there may have been a problem with even noticing the stroke of midnight, considering that hand-wound clocks weren't perfectly synchronized. Midnight was more an idea than a moment. But beginning in the mid-1880s, there were public clocks, in the courthouse and in the Catholic church steeple.

White Lily Factory courtesy of Knoxville History Project

Soon after that, something was up. By the 1890s, perhaps mimicking the churches, individuals were ringing handbells in the streets. Factories would blow their steam whistles. They were operated by a cord, and some of them would just tie the cord down, and let it blow for ten minutes or so. The City Mills factory, later known as White Lily, had the lowest and the loudest. Men fired guns in the air; in some towns in the area, the practice resulted in serious casualties. Boys blew off firecrackers. Some were called "dynamite crackers." Where they real dynamite? It's hard to know, but some caused serious damage. People with houses along the viaducts were vulnerable to mischief. On NYE, 1899, a "dynamite cracker" was tossed into the chimney. “The explosion blew up the grate and brought down a barrel of soot.”

On NYE, 1906, Knoxville was having a party. Staub's Theatre hosted a bizarre show called A Message from Mars, about an alien visiting an immoral Earthling, to improve him. It sounds like a sci-fi version of A Christmas Carol.

“The passing of old and the coming of the new was noisily heralded (in the superlative degree) in Knoxville by hundreds of whistles, bells, firecrackers, guns, and pistols. It was one time that the police didn't cope with the situation.” By 11:55, the factory whistles were blowing all over town, and it was “a perfect din” for more than 10 minutes--”enough ammunition having been wasted to supply the Boer Army a fortnight.” Celebrants were still roaming the streets into the wee hours.

Modern Day New Year’s Eve Ball Drop photo credit Knoxville News Sentinel

Things changed rapidly in the very early 20th century--about the same time, in fact, as a former Knoxvillian named Adolph Ochs, the New York Times publisher who began his career as a journalist at the Knoxville Chronicle office on Market Square, launched the Times Square ball drop, the most famous New Year's Eve ceremony in the world.

Greeting the year 1908 was a big year for midnight noise in downtown Knoxville, by the way. That happened to coincide with the banning of saloons in Knoxville.

Cherokee Country Club circa 1910

After Knoxville's 106 saloons were closed, gunfire in the streets was less common, and hotels, like the big Atkin at Gay and Depot, and later Whittle Springs, began hosting New Year's Eve dinners and dances. Cherokee Country Club was an early celebrant, usually drawing 350 for its posh bash, which included a roaring outdoor fire on the porch, and fireworks. The dinner and dance was for members and guests, but the whole spectacle attracted the public, so many that the transit company ran late-night streetcars to Cherokee.

At midnight, the orchestra didn't play “Auld Land Syne.” They played “Taps.” And that's kind of a funny thing: the song “Auld Lang Syne” was well-known, considered old-fashioned even in the 1800s, much beloved, and sung in public usually more than once a year--but rarely if ever on New Year's Eve. It was probably not widely associated with the holiday until New York orchestra leader Guy Lombardo started performing it on live radio in the late 1920s. And, of course, it fit perfectly.

Lyric Theatre circa 1920

By then, the Lyric Theatre--formerly Staub's—was presenting a more specific New Year's Eve celebration than before: a midnight public extravaganza of dancing and jazz, with a 10-piece orchestra.

It's a bit of a puzzle that New Year's Eve seemed to flower as a time for dancing parties during Prohibition and the Great Depression. When we put on a cardboard top hat, we're evoking that era, when partly thanks to a former Knoxvillian, America started celebrating New Year's Eve as a national event.

By the way, over the years a few famous people have joined us for a New Year's Eve in Knoxville. One was Gen. U.S. Grant, who was staying here a few weeks after the Battle of +-Knoxville. He saw in the new year 1864, which turned out to be a very big year for him. It's not recorded whether he celebrated, publicly or privately. In any case, he probably didn't draw the same crowd as some other northern visitors 74 years later. At Chilhowee Park, the great Harlem jazz bandleader Chick Webb rang in the year 1938 with a New Year's Eve dance, with his 20-year-old singer, Ella Fitzgerald.

We'll have to go a long way to top that one.

For more on modern day New Year’s Eve fun, check out our NYE page – a one stop shop of events!