It didn’t start in recent years, with UT’s Min Kao building, named for the influential Taiwan-born scientist who a fond alumnus of the 1970s, or the Chinese Pavilion, the most popular and significant feature of Knoxville’s 1982 World’s Fair. Tennesseans were always fascinated with all things Asian.

Archeologists excavating the site of a 1790s log cabin often find fragments of China—real China, with Asian imagery, like pagodas. In Knoxville’s first decade, silk garments imported from India were available in local shops. A variety of Chinese teas, including the green tea known as Hyson, were advertised in Knoxville shops in the late 1700s. Hyson is derived from a Chinese word, but well known to the early pioneers who read advertisements for tea in the Knoxville Gazette.

Soon after the Civil War, there were even attempts to grow Chinese tea in the Knoxville area, apparently unsuccessfully. However, in 1869, a prominent grocery opened on Gay Street—later in larger quarters on Market Square—with the intriguing name of Tea Hong.

Running it was an energetic young man with the interesting name of Victor Hugo Sturm. Hardly Chinese, he was nonetheless of "exotic" heritage, described as “a Portuguese Jew from the East”—even though he was said to be born in Germany, and sometimes claimed to be the godson of the French novelist for whom he was named.

Sturm carried a wide variety of groceries, even honey-baked ham, and the first Keebler cookies, from Philadelphia, ever seen in Knoxville—but specialized in teas and coffees, including Chinese green tea. In front of his shop on Market Square was a carving said to be from Peking (Beijing) that he called Johnny Hi-Hi.

By 1871, a competing store was selling Oolong teas and "Young Hyson and Old Hyson" on Gay Street--and real Asian people were occasionally seen in Knoxville, as when a railroad businessman the newspapers called Koopmenschap, said to be “the celebrated Chinese labor contractor,” dined with railroad associates at the Atkin House Hotel, on North Gay Street. “His pigtail queue and pidgin English attracted considerable attention,” reported the Daily Chronicle.

Ironically, about the same time the U.S. government was considering the Chinese Exclusion Act, Americans wanted to keep some of Chinese culture, who by then had an excellent reputation for cleaning clothing (laundry work was one of the few employment opportunities available to Chinese immigrants in the early years), and Chinese laundries came to seem a hallmark of a sophisticated, modern city. In 1880, the Knoxville Daily Chronicle declared, “No city can lay claim to any dignity whatever unless it has a Chinese laundry.” And as it happened, just as new immigrants from China were banned by the government, Knoxville received its first permanent Chinese immigrants, most of them hand-laundry experts, who had shops downtown. Among the first are people we know only by name: Hong Lee, Yee Long, Chung Woo.

Despite the fact that federal law prohibited most of the Chinese immigrants from becoming citizens, the profession became such a familiar feature of Knoxville, that by 1930, the official Knoxville City Directory included a separate category for “Chinese Laundries.”

The Japanese fared no better, as they too were excluded from becoming citizens. Kumi Alderman, Executive Director of the Knoxville Asian Festival, shares some light on a man who became a hero to East Tennessee and all those who love the Great Smoky Mountains: George Masa (born Masahara Iizuka) was born in Japan around 1889 and came to the United States sometime in the early 20th century, likely through San Francisco. Despite most immigrants from Asia staying on the west coast or big east coast cities, Masa made his way to Asheville in 1915. Similarly to many Chinese immigrants, he found a job in the laundry room of the Grove Park Inn, a now historic hotel. He was popular amongst the guests, moving his way into positions that brought him into contact with the wealthy visitors. He took photographs of them and the surrounding mountains, and mailed photos to people like Calvin Coolidge and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. His images of the Smokies helped convince conservationists and philanthropists that these ancient hills were worth protecting. He certainly experienced racism and mistreatment along the way, but Masa made significant contributions to the movement to establish the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. He unfortunately passed a year before the park was officially created, but his photography, connections, and dedication helped preserve the natural beauty of this region for visitors to come. (Read more about George Masa here.)

Asian art and fashion had already caught on in Knoxville. Kimonos were all the rage by 1900, and Asian influences began asserting themselves in architecture and sculpture, most obvious today in Savage Gardens, the ca. 1920 Asian-themed sculpture garden visible from Garden Drive in Fountain City.

By then, the city was also getting a taste of Asian food, albeit in the Americanized form known as Chop Suey. Along with Chow Mein, it became a jazz-age fad, often enjoyed by young people out on the town in the 1920s. In 1932, Knoxville’s first Chinese restaurant opened, specializing in those treats. Located in the space now occupied by the Bistro at the Bijou, The Pagoda’s proprietors were not Chinese, but to make it authentic, they hired a Chinese chef, one Hoey M. Yow.

That restaurant was open when a remarkable Chinese immigrant arrived, one Ben Kwok. A Vanderbilt graduate from Canton, now known as Guangzhou, he opened a bookstore on Gay Street in 1934, selling both English and Chinese-language books. Known as a writer and poet in national Chinese-language newspapers, Kwok became a well-known lecturer in Knoxville on all things Asian, especially in demand at the time of World War II. He lived here until his death in 1951.

Kwok was an exception in many ways. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many of Knoxville’s Asian residents kept to themselves; language was a barrier, and at times they had reason to feel unwelcome.

Public Asian festivals are a relatively recent phenomenon.

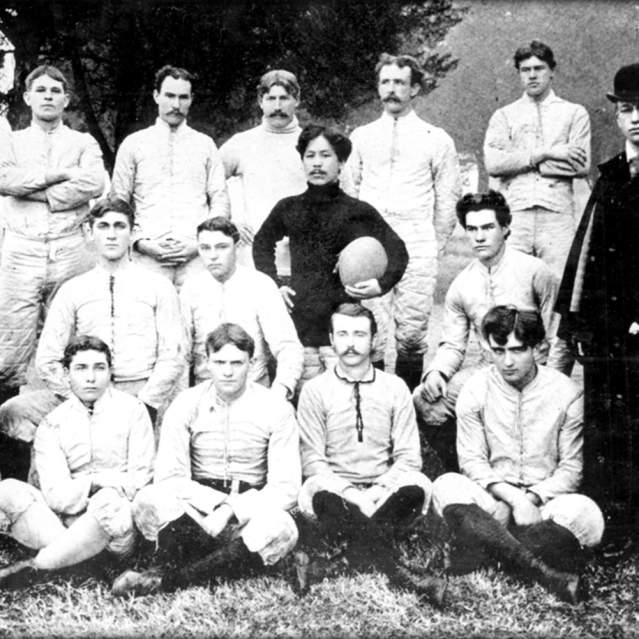

However, one remarkable Asian may have influenced one of East Tennessee’s most festive traditions. Kin Takahashi, a Japanese student who came to Maryville College in the 1880s, had lived in the Oakland area for a year before migrating to East Tennessee with a countryman named Sen Katayama. In California, he’d found something that appealed to him. When he came to Tennessee, he brought with him an object most East Tennesseans had never seen: a football. Takahashi organized Maryville’s first football team, not long before the much-larger university chose to start its own. Some of the first football games ever played in East Tennessee featured the Maryville College Scots, with Takahashi as quarterback.

Knoxville was, at the time, mainly a baseball town. But you never know what’s going to catch on, or who’s going to lead it.

So the Asian Festival is here again, at World’s Fair Park—where 41 years ago, China participated in a World’s Fair for the first time since 1904, bringing amazing cultural artifacts that inspired hundreds of thousands of Americans to wait in four-hour lines to see them—and where some of the most memorable pavilions were those honoring Japan, the Philippines, and South Korea. But the whole city has its own offbeat Asian heritage.

The 10th Annual Knox Asian Festival is August 26th, 2023, from 10:30am-8:00pm.