We take World’s Fair Park for granted, as a venue for concerts and festivals, but next time you’re down there, have a look around. There may be nowhere like it in the world. It’s a pretty extraordinary assemblage of more than a century’s worth of architecture, from mid-Victorian industrial to some hypermodernist, almost experimental work that may have helped lead the way to specialized architecture around the world in the 21st century.

Let’s start with the Sunsphere. It’s been both beloved and ridiculed since its plans were first announced in 1980, but it has become the single most distinctive feature of Knoxville’s skyline. Designing it was an architecture firm with the odd name of Community Tectonics, who proposed a structure honoring the Sun itself, as the source of all energy on Earth. They saw the extraordinarily unusual structure through some very challenging construction issues concerning its site, its safety, the budget, and the immovable deadline. But its basic concept is most often attributed to the firm’s co-founder, an Illinois-born architect named Hubert Bebb (1903-1984) who moved to Gatlinburg because he loved the mountains. Also known for his unusual design of the Great Smokies’ still-controversial modernist 1955 Clingman’s Dome viewing tower, Bebb's involvement makes a personal link between the 1982 World’s Fair and another one 49 years earlier. The same Hubert Bebb was one of several designers of the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933. Because the project resembled in some ways the geodesic dome, the invention of major 20th century American architect Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983), the team invited Fuller himself, then in his mid-80s, to come and consult on the project. Since then, it has developed an identity of its own, as a setting for the 1983 Miss USA pageant and as a gag on a 1998 episode of the Simpsons. Recently renovated, it’s a useful place to tell the story of the growth of Knoxville. Visitors can visit the Sunsphere’s 4th Floor Observation Deck which offers breathtaking 360-degree view stretching from downtown to the Great Smoky Mountains including World’s Fair Park, the Tennessee River and the University of Tennessee Campus.

involvement makes a personal link between the 1982 World’s Fair and another one 49 years earlier. The same Hubert Bebb was one of several designers of the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933. Because the project resembled in some ways the geodesic dome, the invention of major 20th century American architect Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983), the team invited Fuller himself, then in his mid-80s, to come and consult on the project. Since then, it has developed an identity of its own, as a setting for the 1983 Miss USA pageant and as a gag on a 1998 episode of the Simpsons. Recently renovated, it’s a useful place to tell the story of the growth of Knoxville. Visitors can visit the Sunsphere’s 4th Floor Observation Deck which offers breathtaking 360-degree view stretching from downtown to the Great Smoky Mountains including World’s Fair Park, the Tennessee River and the University of Tennessee Campus.

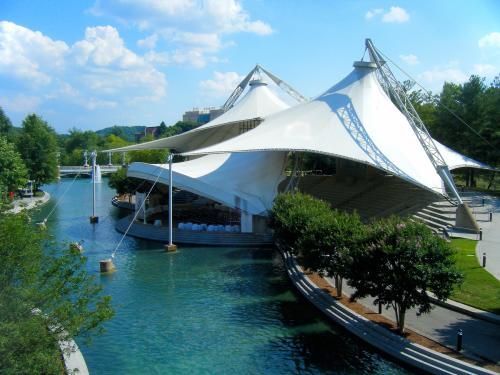

The other most distinctively World’s Fair work of architecture is right near the foot of the Sunsphere. It’s just as daring, if not more so. Paid for by the state government—apparently in lieu of a pavilion--the Tennessee Amphitheater served as an able shelter for a wide variety of performers, from Leon Redbone to Richie Havens to the Ventures to the Warsaw Philharmonic, as well as an Opryland musical troupe’s daily performance of a Broadway-style revue called Sing Tennessee. Although derided as “Dolly’s Bra” during the fair, the building’s unusual appearance is what makes it historic, and maybe internationally significant. It was condemned to be demolished in 2002, during the World's Fair Park redesign; its structural supports were corroding, and it needed expensive work. But a few notable local architects said, “Wait a

minute.” Among them was then-elderly Bruce McCarty, one of Knoxville’s first modernist architects, who had been involved in the design of the fair site in the early 1980s. The Tennessee Amphitheater’s designer was German architectural engineer Horst Berger. Born in 1928, he grew up during the Third Reich but studied engineering at Stuttgart in postwar Germany. He began experimenting with lightweight but rigid “tensile fabric” design in the late 1960s, and by the early 1980s was becoming famous for it. He designed the Hajj Terminal in Jedda about the same time as the Tennessee Amphitheater. His most famous works, like the Denver International Airport and San Diego’s Seaworld Pavilion, came after the Tennessee Amphitheater, but bear a strong family resemblance. The shallow water that almost makes a peninsula of the Amphitheater, an artificial pond located above subterranean Second Creek (which is visible in its natural form on the northern and southern ends of World’s Fair Park) evokes a larger pool known during the fair as the Waters of the World.

minute.” Among them was then-elderly Bruce McCarty, one of Knoxville’s first modernist architects, who had been involved in the design of the fair site in the early 1980s. The Tennessee Amphitheater’s designer was German architectural engineer Horst Berger. Born in 1928, he grew up during the Third Reich but studied engineering at Stuttgart in postwar Germany. He began experimenting with lightweight but rigid “tensile fabric” design in the late 1960s, and by the early 1980s was becoming famous for it. He designed the Hajj Terminal in Jedda about the same time as the Tennessee Amphitheater. His most famous works, like the Denver International Airport and San Diego’s Seaworld Pavilion, came after the Tennessee Amphitheater, but bear a strong family resemblance. The shallow water that almost makes a peninsula of the Amphitheater, an artificial pond located above subterranean Second Creek (which is visible in its natural form on the northern and southern ends of World’s Fair Park) evokes a larger pool known during the fair as the Waters of the World.

Walk under the Clinch Avenue Viaduct—although the deck has been replaced, the basic concrete piers of this bridge that connected downtown’s central business district to West End (now known as Fort Sanders) date back to 1905. Adjacent to the black-painted Marriott is the tall, white-painted TENNESSEAN, now a separate hotel, but its building was built in 1982 to serve administrative and publicity purposes. Both buildings are mostly utilitarian, but the sharp contrast of black and white was a recent touch that makes them more striking than they were at the fair, and almost 21st century modern in appearance. The Court of Flags was the central ceremonial space for the fair, where there were speeches from dignitaries like President Ronald Reagan as well as daily concerts from high-school bands across the nation. The original court was a linear concrete stage, with the flags of each of the 22 nations that participated in the fair. Twenty years after the fair, as part of an ambitious city project, Ross Fowler redesigned much of the fair site, and completely reconfigured the Court of Flags as two circular areas, on either side of an elaborate fountain feature that’s especially popular with kids in the summer as the largest splashpad in the city.

Adjacent to the black-painted Marriott is the tall, white-painted TENNESSEAN, now a separate hotel, but its building was built in 1982 to serve administrative and publicity purposes. Both buildings are mostly utilitarian, but the sharp contrast of black and white was a recent touch that makes them more striking than they were at the fair, and almost 21st century modern in appearance. The Court of Flags was the central ceremonial space for the fair, where there were speeches from dignitaries like President Ronald Reagan as well as daily concerts from high-school bands across the nation. The original court was a linear concrete stage, with the flags of each of the 22 nations that participated in the fair. Twenty years after the fair, as part of an ambitious city project, Ross Fowler redesigned much of the fair site, and completely reconfigured the Court of Flags as two circular areas, on either side of an elaborate fountain feature that’s especially popular with kids in the summer as the largest splashpad in the city.

Immediately to the north is a train station that many of these soldiers saw as they left for training. The L&N Station, built in 1905, saw passenger trains come and go every day and night until the last one departed in 1968. At the time of its completion, the station was central to the L&N’s service to Cincinnati, Louisville, Nashville, and Atlanta. Its designer reportedly had the mandate to make the station much more eye-catching than the brand-new Southern Railway terminal a few blocks to the northeast. Often compared to a “chateau,” is said to resemble the elaborate styles associated with the Flemish Renaissance. The design of brick and marble, accented with ironwork and stained glass, is attributed to Irish immigrant Richard Montfort (1854-1931).

Montfort was trained at the Royal Academy in Dublin in engineering. But Montfort made his career working for L&N in Louisville, KY, and developed a reputation as an architect, especially regarding his two best-known works—this one, and Nashville’s Union Station. The building and its stained-glass windows are described in detail in James Agee’s Pulitzer-winning novel, A Death in the Family, set in 1916. Celebrities sometimes caused a stir here, none more than actor John Barrymore, who was greeted by a crowd when he stepped off his train here in 1940 to perform at the Bijou Theatre. After it closed in 1968, the station was mostly empty for many years, but rehabbed for the 1982 World’s Fair, it hosted offices and restaurants. Perhaps the crown jewel of the fair’s unusual reputation for historic preservation, it drew more attention than most of the modern buildings. The New Yorker’s A.J. Kahn ignored the fair’s modernist styles but called the L&N “beguiling.” After the fair, it served several purposes, usually hosting at least one restaurant, but in 2011 it was painstakingly restored again, bringing back more of its original 1905 look, and converted into the L&N Stem Academy, a specialized public high school, the purpose it serves today. (Because it’s a school, visiting the building requires special permission.)

Montfort was trained at the Royal Academy in Dublin in engineering. But Montfort made his career working for L&N in Louisville, KY, and developed a reputation as an architect, especially regarding his two best-known works—this one, and Nashville’s Union Station. The building and its stained-glass windows are described in detail in James Agee’s Pulitzer-winning novel, A Death in the Family, set in 1916. Celebrities sometimes caused a stir here, none more than actor John Barrymore, who was greeted by a crowd when he stepped off his train here in 1940 to perform at the Bijou Theatre. After it closed in 1968, the station was mostly empty for many years, but rehabbed for the 1982 World’s Fair, it hosted offices and restaurants. Perhaps the crown jewel of the fair’s unusual reputation for historic preservation, it drew more attention than most of the modern buildings. The New Yorker’s A.J. Kahn ignored the fair’s modernist styles but called the L&N “beguiling.” After the fair, it served several purposes, usually hosting at least one restaurant, but in 2011 it was painstakingly restored again, bringing back more of its original 1905 look, and converted into the L&N Stem Academy, a specialized public high school, the purpose it serves today. (Because it’s a school, visiting the building requires special permission.)

Nearby is a more solemn later addition: The East Tennessee Veterans Memorial. Designed by Knoxville architect Lee Ingram, the cluster of 32 granite pylons like enormous gravestones bear the inscribed names of over 6,200 soldiers from East Tennessee who have died in wars since World War I. Also here is a 27-foot-tall bell tower, with President Franklin Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms. Since its completion in 2008, the cluster of monuments has been a focus of Memorial Day ceremonies, when the names are read aloud, one by one.

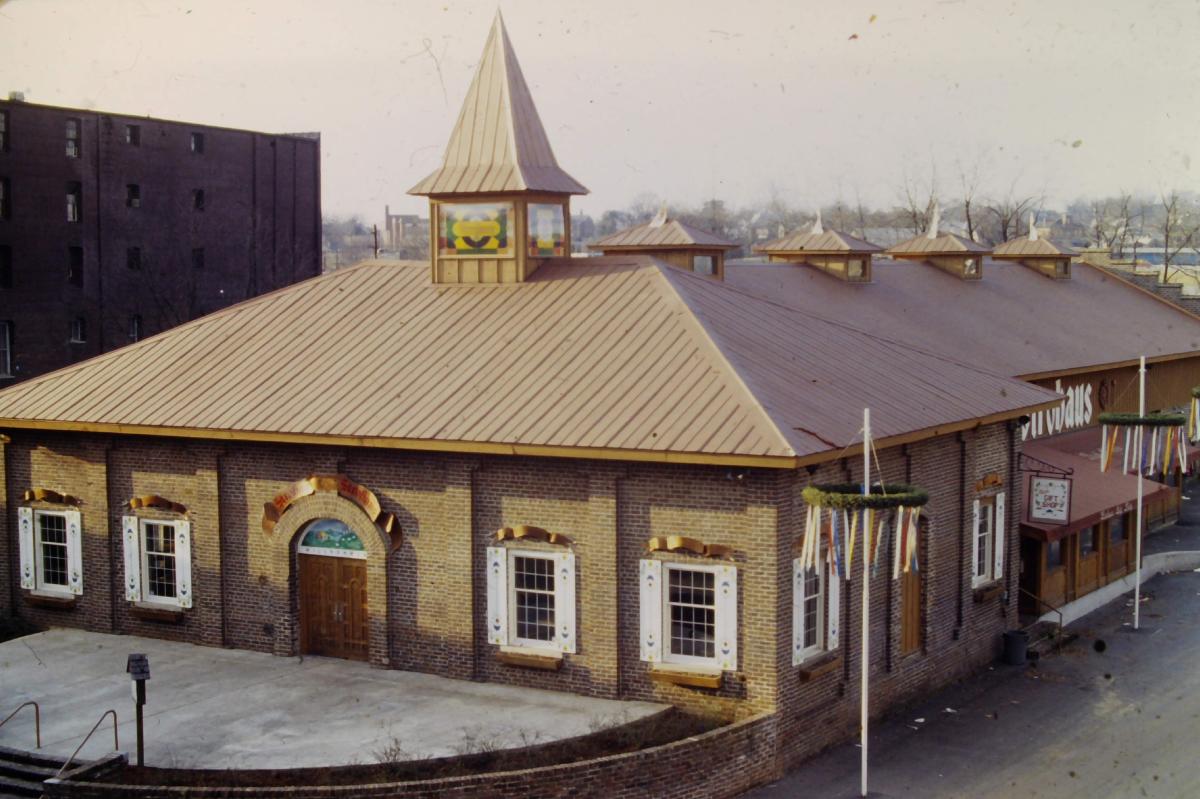

Under the Western Avenue Viaduct (formerly the Asylum Avenue Viaduct) is the large brick building that’s by far the oldest on the site. Its bell tower might make it resemble a school or church, but it’s an iron foundry, part of the Knoxville Iron Company’s plant on this site. It’s been described as a nail factory, but because it was just part of a multi-building plant, its building date is uncertain, variously given as 1865 or 1871.

During the fair, it was the festive Strohaus, sponsored by then-popular Stroh’s Beer, which wanted to convey a German beer-hall ambience, serving food and beer to large crowds all day, with dancing to polka bands at night. (By a fun coincidence, the Knoxville Brewery, perhaps Knoxville’s first beer factory, emerged just after the Civil War along First Creek immediately to west in the 1860s, and coexisted with this building, likely counting foundry.

Walk up the hill to the southwest, and to the right you’ll see the “Victorian Houses,” the generic name given to seven modest-sized wooden houses from the 1890s. These modest but still fashionable houses, perhaps the “starter homes” of their era, were homes to young professors and ministers around the turn of the century, but some were in such poor repair in the 1970s that they were considered for demolition. They were saved and reused for the fair as small galleries and shops. Today, some of them are residences.

Walk up the hill to the southwest, and to the right you’ll see the “Victorian Houses,” the generic name given to seven modest-sized wooden houses from the 1890s. These modest but still fashionable houses, perhaps the “starter homes” of their era, were homes to young professors and ministers around the turn of the century, but some were in such poor repair in the 1970s that they were considered for demolition. They were saved and reused for the fair as small galleries and shops. Today, some of them are residences.

As obvious as a Greek temple, the white Knoxville Museum of Art was the first major building to be built in the park after the World’s Fair. The culmination of about a century of attempts to launch a Knoxville art museum, it was one of the last designs of New York architect Edward Larrabee Barnes (1915-2004), and makes good use of Tennessee marble, which has a pink cast to it. It stands on the site of the Japan pavilion, which was notable for its artistic painting robot. The KMA has hosted a few major shows over the years, featuring works by sculptor Auguste Rodin as well as pop artist Andy Warhol, but today may be best known for its collection of the work of Knoxville-born artist Beauford Delaney; for its chronological historical exhibit of East Tennessee art, “Higher Ground; and for its public musical events, including some associated with the annual Big Ears Festival.

Next door is the Candy Factory, which was a real candy factory when it was completed in 1916, when it was the headquarters of Littlefield and Steere, the largest and most ambitious of several candy manufacturers in Knoxville. Its architect is unknown, but it’s notable for its access to both the railroad level, on the very bottom, and the street level, on its third floor. Such multi-tier architecture was once common in hilly downtown. During their approximately 17 years here, Littlefield and Steere developed a national and even international market for their diverse variety of candies, including chocolates, marshmallows, and bon bons.

It closed during the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the building, briefly refitted to serve as a brewery, served mainly as a warehouse for decades until the 1982 World’s Fair, when knowledge of its origin inspired planners to revive it as the Candy Factory, with a small candy manufacturing facility as well as several shops and restaurants, and, on the top floor, the exotic Flamingo Lounge. When vague suggestions of its destiny as a residential building seemed to evaporate, the city made it available for use by art groups for several years, when it witnessed gallery openings, ballet performances, and poetry readings. As much of that activity moved downtown, its time of condo development finally arrived, and by 2005 it was a popular residential building. For years, it was also home to the Chocolate Factory, which, by some variations on the name, remained in business there for more than 30 years, longer than the original Littlefield & Steere era. Today, visitors can stop into Tall Man Toys & Comics on the Clinch Street level – one of the largest Funko Pop dealers in the southeast.

South of Clinch Avenue is the field long known as the South Lawn, which has seen hundreds of concerts and festivals in the last 40 years. Maybe the biggest surprise at World’s Fair Park is something most visitors never see. It’s out of the way, in a copse of trees on the south end of the South Lawn, but accessible from the steps up from the corner of Cumberland and 11th Street.

This one is not a building, but an oversized bronze sculpture. It is, in fact, the only statue of pianist and composer Sergei Rachmaninoff in the Western Hemisphere. What’s he doing here? An obscure Russian sculptor named Viktor Bokarov idolized Rachmaninoff, and created the statue in the 1990s. He wanted to see it placed in the city that greeted the great composer’s final performance. In February 1943, Rachmaninoff performed a dramatically impressive piano recital before a large crowd at UT’s Alumni Auditorium. At the time, Knoxville’s old classical-music venues were in poor repair, and UT’s relatively new auditorium became the go-to venue for most classical concerts. Unaware that he was mortally ill with cancer, Rachmaninoff finished the concert, did an encore, and then canceled the rest of his American tour. Then in the process of becoming an American citizen, he died in California a few weeks later. Almost half a century later, somewhere in Russia, Viktor Bokarov finished the plaster version of his sculpture called “The Final Concert” and somehow shipped it to Knoxville. It stood on a stairway landing in a large residence on Gay Street for several years, before 2003, when thanks to a community effort it was finally bronzed. UT couldn’t find a place for it, so it was installed in the then-transitional World’s Fair Park, just as its redesign was being completed. The melancholy-looking composer faces UT’s Hill, where the concert took place. It’s unknown whether the elusive Bokarov has ever seen the statue in its permanent home. The park’s walkways lead you over a bridge overlooking an artificial waterfall. It’s roughly the site of the U.S. Pavilion, a six-story wedge-shaped modernist building of steel, concrete, and glass, including an adjacent IMAX theater. It was all intended to be permanent, but after a few public events, and several seemingly promising plans for it that came to naught, it was finally demolished in 1991.

The largest building on World’s Fair Park is the Knoxville Convention Center, with its impressive modernist side facing toward the park. Designed by McCarty Holsaple McCarty, who have designed most of Knoxville’s largest modernist buildings, and led the overall park plan in 1982--in partnership with Thompson, Ventulet, Stainback & Associates (TVS) of Atlanta, famous for the Omni Coliseum and the Georgia Dome. The convention center has witnessed hundreds of high-profile events over the years, from national bowling tournaments to tech conventions to several Destination Imagination competitions for young inventors, to a multi-day Antiques Road Show series for PBS.

Constantly evolving World’s Fair Park looks very different from its appearance in 1982, but honors that memory enough to merit its name. Few historic exposition sites in the world seem as active and diverse and relevant to the newest eras as this one does, especially on a sunny day.

Head here for more on World’s Fair 40th celebrations, exhibits, and events!